Quest for the Tree Kangaroo: An Expedition to the Cloud Forest of Papua New Guinea

(Scientists in the Field Series)

Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0618496416

Note: As part of my work researching and writing this book—in addition to the library research, copious field notes, and interviews conducted in advance and in the field-I write a narrative every night to keep the events of each day fresh.

These entries are not written specially for kids. They contain more advanced vocabulary and more mature content than the other documents on this website.

16 March—Cairns, Australia to Lae, Papua New Guinea

Leaving Australia for Lae, devastating news: drilling in the National Arctic Wildlife Refuge. It hasn’t gone through both houses of Congress yet, but the very prospect sickens us. Later today we will arrive in Papua New Guinea-a country that our leaders consider “backward” if not outright “savage”-where tomorrow we will be present at a meeting with the provincial government to discuss creation of the nation’s first conservation area based on the Conservation Areas Act.

Leaving Australia for Lae, devastating news: drilling in the National Arctic Wildlife Refuge. It hasn’t gone through both houses of Congress yet, but the very prospect sickens us. Later today we will arrive in Papua New Guinea-a country that our leaders consider “backward” if not outright “savage”-where tomorrow we will be present at a meeting with the provincial government to discuss creation of the nation’s first conservation area based on the Conservation Areas Act.

The irony isn’t lost on Lisa. “They are creating the future for their country. How great they have land tenure-how great they have the power that we don’t have.”

Poll after poll confirms that the vast majority of Americans don’t want drilling in the National Arctic Wildlife Refuge. Yet drilling could go forward because the provision was tacked on to another unrelated bill in Congress. This can’t happen in Papua New Guinea. The land is owned by clans. The people themselves set the restrictions for what goes on on their lands.

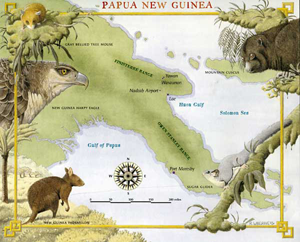

The Conservation Areas Act was enacted at Independence, but up top now folks used the Wildlife Management Areas to protect land. The CAA is more restrictive, if landowners agree on it. The Wildlife Management Areas really only protect the animals, not the land they depend on-mining and timber extraction is still permitted. This year, the goal is to submit the documentation-map, inventory, etc. —proposing the watershed where the study is sited for a conservation area.

We spoke of these things on the long journey from Cairns to Port Moresby, from Port Moresby to Lae. Having already lost my scissors to “Security” in Australia (don’t you feel much more secure now that I can’t cut my own toenails?) now I lose my nail file in PNG. We travel all day-customs again and again-the hurdles of Lisa’s overweight luggage and Nic’s film, and possibly contraband energy bars and fruit leather, weighing the chances of losing our bags and wondering whether the Education Team’s equipment will ever turn up.

When Nic was 14, his dad, a teacher for UNESCO, was transferred to PNG. Before the family left, they went to the consulate in Paris to get their visas. When the clerk finally handed the documents over, Nic remembers he said this: “Here you go-you poor bastard.”

We are flying away from abundance and air conditioning—talk turns to whether we will need to buy an extra jar of peanut butter when Nic went for seconds of the breakfast pancakes-and we are flying towards wildness and wonder.

Below us, at last, we see the Markham Valley and the Markham River which causes speciation and divides the mainland from the Huon Peninsula, where we’re headed. We see green-grasslands, trees, mountains-and hazy blue sky. There is only one road: Lae.

17 March—Lae

A few notes on our hotel, The Melanesian, home for the next few days:

We discover to our horror that the hotel costs a lot-Nic and I aren’t sure about our conversion rates of Kina to Dollars, but it might be as high as $100, and is certainly going to cost at least $60, every night. It seems nicer than we need, with a pool and flowered patio, a tableclothed restaurant, a doorman. Our room, which Nic and I share (it would have been me and Lisa but Nic is too wary of Joel’s very contagious, runny, sneezy cold, so Lisa, who probably gave it to him, is rooming with Joel instead) has two perfectly fine beds, one chair, a TV we will never turn on, a closet, a desk, and an icy air conditioner which inexplicably emits a single, piercing, smoke-alarm-like shriek every few hours during the night.

The room also has a “Chinese” bathroom-the kind with half a moldy shower curtain that blows inwards when you turn on the water, so the water doesn’t land on you, but instead goes all over the floor. The sink drips water on to the floor seconds after you turn on the faucet, along with the toothpaste suds you just spat out. There is also, for some reason, a blunt, rusty, inch-long nail sticking up out of the floor inches from the shower, which miraculously neither of us has stepped on yet. The toilet flushed beautifully until we discovered the Weeta-Bix at the breakfast buffet. Roughly 24 hours after eating Weeta-Bix, I made the unfortunate discovery that the plumbing wasn’t up to the challenge-a problem I had to confess to Nic before ceding him the bathroom for his morning ablutions. “Well, you could reach down there and try to break it up,” Nic suggested unhelpfully. “For $100 a night,” I told him, “I am NOT going to reach my arms into a Third World toilet.”

Meeting, 10 a.m., at the Government Building:

We’re in the only tall building in town, in a barely air conditioned boardroom featuring stained carpeting and a waste basket of watery brown fluid beneath a leaking coffee maker. We sit around two long tables which have been pushed together. There are 19 of us, including: Lisa, Joel, Toby, Gabriel, John, former Member of Parliament Ginson Saonu, representatives from Conservation International and the Department of Conservation, the provincial administrator, the program advisor for education, and the Provincial Governor. He’s the only one of us wearing a suit, which is brown, with a white shirt and yellow and brown necktie-a big man with wide cheekbones and a broad nose and a bushy moustache.

We’re in the only tall building in town, in a barely air conditioned boardroom featuring stained carpeting and a waste basket of watery brown fluid beneath a leaking coffee maker. We sit around two long tables which have been pushed together. There are 19 of us, including: Lisa, Joel, Toby, Gabriel, John, former Member of Parliament Ginson Saonu, representatives from Conservation International and the Department of Conservation, the provincial administrator, the program advisor for education, and the Provincial Governor. He’s the only one of us wearing a suit, which is brown, with a white shirt and yellow and brown necktie-a big man with wide cheekbones and a broad nose and a bushy moustache.

Ginson-Lisa has known him since she began her study in 1986-begins with what sounds like a blessing: “This meeting,” he said “is unlike other government meetings. Many meetings are about development. This meeting is about creation.

“In the name of development, we destroy God’s creation,” Ginson said softly, humbly. “God created the plants and animals and those things, and created us to look after them.”

With that, he introduced Lisa.

“We’ve been quietly working since 1996 with your tree kangaroos,” she said. “It’s an honor to meet with you today.”

She described how the project does not work alone, but with many other organizations, both in PNG and the US and elsewhere. She described how she first came here: “I studied Matchie’s Tree Kangaroos in zoos in the US and wanted to help them in the wild” and noted “Matchie’s Tree Kangaroos only live in the Huon Peninsula. You are the lucky ones!” She told how her dream was to learn the species’ habits and landscape, its genetics and diet-and how “I was told by scientists in the states this kind of work could not be done”-yet managed, with the help of the landholders, to capture, radio collar and release three Matchie’s tree kangaroos and track them for three months-the first GPS radio collars ever for any animal in PNG. She told of the biological surveys, the education projects, the Bug Club, the teachers’ scholarships, all brought here by the TKCP, all thanks to the tree kangaroos.

“I really believe the future of conservation is with kids,” she said. “The more kids around the world understand the importance of protecting plants and animals, the better off we’ll be.” And she spoke of her hope to create a Conservation Area in the area we’ll be working: “We are hoping it could be a model for other areas for protecting habitat. “So we come to ask: how can we assist you? How can we partner with you? We come to you today to find out how we can work together for this conservation area.”

The CI representative spoke. The Administrator spoke. And finally the Governor himself:

“Let me thank you, Dr. Dabek, thank you from the bottom of my heart for what you have done. It is a small world. Whatever we do here influences you-not only human beings but plants and animals, too. We need to help each other.

“This tree kangaroo is the tree kangaroo I knew as a kid-she is like our identity. But if we do not care, they will all be wiped away. But in the long run, they will be here-so we will all survive. That we are the only place in the whole wide world with this tree kangaroo-this is news to me. That is news for the day.

“My government will support this project whole-heartedly.” He even planned, he announced, to establish a Board of Conservation within the provincial government. “Would you,” he asked Lisa, “be willing to be part of it?”

“I would be honored,” said Lisa.

18 March-Lae

Paradise is hot as hell. It must be more than 90 degrees in the shade, 90 percent humidity. But this is bliss. Today with Lisa, Nic and I visit Rainforest Habitat, a zoo on the university campus just outside of town. Thirty tree kangaroos of four species live in spacious, clean, interesting cages here-the largest collection of tree kangaroos in the world. And this is the only collection to house the Grizzled Tree Kangaroo-a pair with a tiny pinkie joey in the female’s pouch. At five months he will poke his head out for the first time-a stage at which “they look like little Chihuahuas,” said Lisa.

Paradise is hot as hell. It must be more than 90 degrees in the shade, 90 percent humidity. But this is bliss. Today with Lisa, Nic and I visit Rainforest Habitat, a zoo on the university campus just outside of town. Thirty tree kangaroos of four species live in spacious, clean, interesting cages here-the largest collection of tree kangaroos in the world. And this is the only collection to house the Grizzled Tree Kangaroo-a pair with a tiny pinkie joey in the female’s pouch. At five months he will poke his head out for the first time-a stage at which “they look like little Chihuahuas,” said Lisa.

With our squat, sweet hostess Margaret, we tour the place: first of course the tree kangaroos: so many beautiful Matchie’s. “These guys’ ears are way furrier than the Lumhotlz,” Lisa says. It is wonderful to see them so close. Their eyes defy description: they are neither brown nor blue, but both at once- tree bark and sky, earth and ocean-like opals.

“They look like nothing else-and everything else!” I say to Lisa, and she replies, “It’s funny to see which animals people say they remind them of. Some people even say the Matschie’s reminds them of a pig, because of the pink nose.” She gives me that sentence like a gift.

There are a number of Goodfellow’s Tree Kangaroos as well-shining creatures with red-chestnut fur marbled with gold. The exceptionally long tail looks like that of some jungle cat. These tree kangaroos are very friendly. A female let me stroke her belly for 15 minutes; I wondered if I could put my hand in her pouch, but I thought it too forward. The Doria’s tail is far shorter, the ears set further back on the head, and the body is squat and powerful-looking-almost like a wolverine.

We visit Muruk-this is my favorite Tok Pisin word, though I had read earlier that Cassowary already came from the “Papuan” for Horned (kasu) Head (weri). The Northern and Dwarf cassowary live here at the zoo, although 3 species actually inhabit PNG. The dwarf is only a bit over 4 feet high, with a black face and triangular casque, mahogany eyes, cobalt neck and a tough of lavender at the cheek, with hot pink down the side of the lower neck. Despite its smaller size, it kills people, too, just like its larger brethren: two years ago, one kicked an old woman to death in the village of Warren. The Dwarf, or Bennett’s, lives in montane forests from 1,000-3,000 meters; the single-wattled of Northern Cassowary in lowlands. It has a greenish casque, turquoise neck, cobalt face and curious golden eyes topped with eyebrow hairs. A single blue wattle hangs form the neck like a bead, and down flower part of the neck stretches a swatch of red, warty flesh, like the juicy seeds of some tropical fruit. The body plumage is jet black and hangs like hair.

Muruk’s voice is deep and booming like a ceremonial drum, important and powerful as a lion’s roar-and sometimes it does sound like a roaring lion. Later, Ishimu, one of the keepers here, tells me that in the villages, when the northern cassowary utters his first coughing roar of the day, the people know it is 8:30 a.m. “A natural alarm clock,” he said, “like a really big rooster crowing.”

Other treasures: in the sweltering gift shop, a 6-foot-long olive python named Pedro is coiling around the class countertop above the tortoise shell pendants. I stoke him uneventfully. (Later I find out that he bites.) In the Aviary, a Dusky Lory parrot licks the sweat from my face with gentleness and determined patience. Nic doesn’t like it. When Lisa tries to remove the bird, he screams piercingly in my ear and bites. Later he voluntarily moves over to Lisa’s face and vacuums her, too.

Nic photos many great birds. Among them: the pitta hui-or poison bird, the only known bird with toxic feathers. Interestingly its warning coloration, orange and black, is like that of the Monarch butterfly and some poison dart frogs, as if these colors are a universal language, understood as toxic by different species around the world.

Nic also got great photos of several Birds of Paradise-they surprise at every turn, from the amazing tails and startling colors to the sounds they make: the Brown Sicklebill Bird of Paradise utters a machine gun like noise to attract females. The first specimens of Birds of Paradise sent to Europe were dead birds used in native headdresses, with the wings cut off-so Europeans though these birds had no wings. They were believed to float through the air like thistledown.

21 March — Lae

Nic and I spent a third day at Rainforest Habitat-hot, humid, full of mosquitoes, and thrilling beyond belief to be so close to tree kangaroos, among a family of Goodfellows, or in an outdoor enclosure with a Doria’s and her male offspring.

Nic and I spent a third day at Rainforest Habitat-hot, humid, full of mosquitoes, and thrilling beyond belief to be so close to tree kangaroos, among a family of Goodfellows, or in an outdoor enclosure with a Doria’s and her male offspring.

Drama on the project: none of us but Nic has escaped some sort of airplane disaster coming over here. My outgoing flight from Manchester was cancelled and delayed me nearly two days; Joel and Lisa, sick with their colds, were late coming in to LA and to Cairns. But worse, Holly, the project veterinarian-without whom we cannot leave for the field-was stuck in Port Morseby because the plane’s jet fuel was contaminated with sea water. She only just got in today, as did Christine, the zookeeper-whose bags are still, at 10:45 the night before our scheduled 7 a.m. departure, missing in action. And poor Robin is still stuck in Australia, also because of bad fuel. Will our expedition be able to leave tomorrow?

22 March—Lae and (possibly) enroute to Yawan

We rise at 6 for our Mission Aviation Fellowship flight, which is not at 7 at all, but unscheduled. We are a stop along the route. What route? Depends on what’s going on that particular day.

We load our stuff onto the Bos-A-Nova bus: 10 white Dittyman bags, 3 large backpacks, 5 cardboard boxes, 3 hard sided pelican bags, 20 liters of kerosene and all our personal gear….

This joins a boatload of stuff that’s already waiting for us at the airport. It is overwhelming to realize that all this gear is going on a three-day hike to a remote camp at 10,000 feet on top of people’s heads.

No one expects us to leave at 7, but by 10:30 when the plane still isn’t there Lisa begins to make inquiries. The plane is in Tep Tep. It had been supposed to fly to Isan, drop cargo there, then pick up the TKCP Education Team and take them to Bungawat-just one of the many legs of the plane’s series of journeys before it could get to us and to Yawan. But because of clouds, the plane never made it to Isan at all. It diverted to Tep Tap.

We wait in the cement and cinderblock airport with its barely spinning fans, sitting in dirty plastic chairs. We go over lists of veterinary and scientific supplies. We talk of pets and lovers and spouses.

11:30: Reports have it the whole area between Isan and Tep Tep is cloudy. “But they’re going to try to get to Yawan later this afternoon,” says Lisa. The Isan airstrip is only 400 meters long with a 2,000 foot drop on either side.

Joel was once stuck in Yawan for three weeks because of delays and cancellations like this. “There always has to be a backup plan,” Lisa says. Ours is, if we don’t get out today, we’ll use Kiunga airlines’s 4-seater Cessna to ferry us and our stuff over the course of repeated flights to Yawan.

We explore the airport’s dubious restaurant and investigate its mysterious sandwiches, which Nic notes could cause explosive diarrhea on the plane. We buy cheese twists instead. There is a gift shop the size of a closet with bags and carvings.

It’s a good time to learn more about people’s stories. As we wait, I interview Holly: the daughter of a Navy dad, she grew up moving constantly-she lived in Japan and Italy, the east and west coast of the US, all the while reveling in the outdoors and nature. Veterinary practice was a natural choice for her career. She’s worked in Alaska assisting in a study of reindeer migration, in Australia rehabilitating wedge-tailed eagles, tiny joeys, giant fruit bats; and in Kenya trying to implant bongo embryo into eland to try to restock the species.

I learn how Christine, now 36, had been diverted from doctoring to care instead for animals. A brilliant student with a love of biology, she graduated from Rutgers in 1990 and asked for a one-year’s deferment from medical school to intern for a year at Minneapolis Zoo-and never left. No wonder: there she cares for Matchie’s tree kangaroos, binturongs, clouded leopards, fishing cats.

I learn how Toby, 29, got his master’s in herpetology working on the orange-tailed skink-which was only discovered in 1998! In 2004 he caught 120 of them and described for the first time their range, morphology and growth rates. I am privileged to be joining such an extraordinary group of people.

12:30: An update on all the moving pieces: The Cairns to Port Moresby flight took off, but Robin wasn’t on the passenger list! Christine’s bags are now in Brisbane. The plane is still in Tep Tep.

Lisa tells us the gruesome story of the leech that got in her eye. She was up in the forest, hiking, and had her glasses on-but she felt something drop in her eye-a drop of water, perhaps with a speck. She thought little of it. But her eye continued to bother her and finally that night in camp she asked the expedition vet to have look. She pulled the leech out with tweezers. PS: two other people on previous expeditions have had leeches stuck in their eyes. I think: Oh. My. God.

1:10: The plane has left Tep Tep for Isan. The Education team will be able to go on to Bungawat after all. But what about us?

We’re now in the air-conditioned Mission Aviation Fellowship office with an angel named Margaret, who is providing us with updates on Robin’s whereabouts (unknown), Christine’s baggage (headed our way but unlikely to catch up) and the MAF plane. We note the closings on 10 airstrips, recorded in magic marker on an erasable board: two due to long grass. One does not have a windsock. Another lists a windsock that is malfunctioning (?)

1:15: Robin is on the plane. As for our flight, says Lisa, “They don’t seem to be worried. We’ll see if we get out. It will be a couple of hours.”

Not wanting to be a nuisance to Margaret, we migrate to the Paradise Club-not knowing what it is or who it is for, but we suspect it’s not for the likes of us. It is aptly named. There is air conditioning. Also free bananas, a refrigerator with cheese, crackers and snack mix. We are quickly discovered and evicted but not before devouring lunch.

When we emerge to the sweltering waiting room, we discover the dirty plastic chairs are now all occupied by other would-be passengers. We sit on the concrete floor. Some of us play cards to pass the time. Then we get the news:

2:30: The plane is here! We move outside and see it is being fueled with Shell-the brand that was contaminated with sea water.

2:45: “Yeah! We’re going!” says Lisa. We move outside to the edge of the runway, into the sun.

2:50: “What’s the second option if we can’t get to Yawan?” the pilot asks Lisa. There is rain in the area, he says-but it could stop. He tells us he is going to take off-but can he land? His answer: “I can’t promise.”

3:00: We’re still waiting on the tarmac and receive another update: The weather is not looking good. Because of bad weather, the education team actually got flown to Sepmunga instead of Bungawat.

3:10: We board. The Twin Otter has 12 seats. The windows on the left side of the plane are obscured by two huge boards-the blackboard for the Yawan school. The pilot asks, “Does anybody have breathing problems-like asthma?” Both Lisa and Toby answer yes. “If the weather is bad and we have to go above 14,000, we’ll need to have an oxygen bottle nearby.” (At 14,000 feet, even if the pilot can’t see, he can’t crash into a mountain. The highlands are littered with World War II pilots who hadn’t yet made this important discovery.) The plane is stiflingly hot. The pilot points out the air sick bags.

3:25: We’re off! Below us, no roads, no houses. Just mountains-its forest burned away-and kunai grass. A rainbow. Small villages. Thatched houses. Cloud. Then, forest.

The spines of the mountains are jagged as Stegosaurus’ back-and clad in trees. Except where there were landslides-brown or grassy. We bank. Below us, a huge waterfall cascades down a verdant mountain. Thatched roof houses with bright gardens. Yawan.

3:50 We land and applaud.

* * *

Yawan is unbelievably gorgeous. The beautiful houses are built on short stilts, with woven walls and palm roofs. Banana plants and gardens abound: New Guinea impatiens, coleus, daisy-like orange flowers.

About 80 people are on the landing strip to meet us: handsome, strong people in filthy, tattered Western clothes and no shoes and huge white (and also betel-stained red) smiles. Some of the women have facial tattoos-starbursts on the cheeks, or short lines on the forehead.

Dono hugs each member of the team. I have heard so much about Dono from Lisa and Joel, and imagined him an important part of the story. But he and his wife Annie are leaving on the same plane we arrived on-heading with their teenage daughter to the doctor’s in Lae. She has some kind of woman’s problem. Because of this, there will be no sing-sing to welcome us. Nic and I are disappointed because this would be wonderful for the book. We worry about how to present the village as the culturally rich place it is, when young Americans’ eyes will surely focus on the people’s dirty, ragged clothing.

I love the sounds of the village, like so many others I have visited-sounds of clucking chickens and peeping chicks and voices murmuring words I can’t understand. We visit the house of Dono’s sister, who will be taking care of Dono and Annie’s other kids while they are away. I speak with Pekison Kusso, the elementary school’s 2nd grade teacher, sitting with the others by the smoking fire. We share roasted corn-and fleas. Before we crawl into our sleeping bags on the floor, Lisa and I rub Deet all over our legs that night before bed. “Other women are applying moisturizer this evening,” I comment.

23 March-Yawan to Towet

Great morning interviewing teachers and students-the kids, to our surprise and delight, wearing traditional dress-a once-a-week event at school that we just happened to catch. How lucky! The kids look fabulous in their bark cloth capes and grass skirts. And amazingly, we recoup another “lost” part of our story, too: Two elders offer us a song and dance as our send-off from Yawan to Towet and into the forest.

Joshua Nimoniong and Bonyepe Dingya dress in bark cloth and loincloths, their faces and bodies splashed with white ash. “The color reflects what comes from our hearts,” Joshua tells us through Gabriel. In Tok Pisin, the word for this heartfelt feeling is “won-man” or “one-man”-expressing that Yawan’s people and we foreigners with the TKCP are all in it together. Black charcoal accentuates the men’s expressive eyes. And topping off each outfit is a spectacular necklace of sea shells (it is a 10-hour walk from here to the sea) and dog teeth-and even more spectacular hats.

Each hat is different: both built from a scaffolding of bamboo decorated with the red feathers of the female Eclectus parrot and the tall dark feathers of the hornbill. The hats both have moving parts. The men secured springs-from old cars in Lae-so that as they dip their knees in the dance, the feather in the hat rocks back and forth. “It makes the others want to join in the dance,” explains Joshua.

The two men dance and sing and beat out the rhythm to their song on their kundu drums, decorated with the fur of the cuscus. The beat, the melody, the moving hats-it all does make you want to join in. But what is the song about?

Joshua explains:

“The song is about going into the bush. It’s about the flowers, the trees, the mosses, and about appreciating and respecting them. It’s an old song we sing when we go into the forest-it helps us to keep our thoughts on the forest. Our thoughts are on the forest, too, for this afternoon we begin the first leg of our 3-day journey to the cloud forest-beginning with the three hour hike up muddy 45 degree slopes to the village of Towet.

* * *

For the hike, to make it easier for me to reach my water bottle, Lisa suggests I try her spare Platypus, which is worn around the hips and much cooler than a backpack. I must have fastened incorrectly and worn it like a corset. I can’t breathe. No matter how hard I try I cannot get enough oxygen into my lungs. I remember my father dying of lung cancer, his last hours gasping for breath as his lungs filled with blood. For two hours I wondered quietly whether I might be having a heart attack. I wonder if everyone else is feeling this bad. Not Nic: he bounds ahead like a mountain goat, cheerful with 25 pounds of gear on his back. Not Lisa: she’s smiling from ear to ear. In back of Lisa and me, the others seem fine, too. The local people, of course, are having no problems at all, walking barefoot-to them, this is a mere stroll.

I hoped no one would notice I was having trouble. But apparently they did: within 30 minutes of starting out, Lisa decreed the borrowed Platypus had to come off —and handed it to a 6-year-old. The minute we stopped walking I was fine-not particularly tired, no sore muscles, even. This is all very odd.

24 March-Towet to Kotem River-9 hour hike

The first three hours are the worst-so steep my heart is pounding in my chest like some crazy animal trying to get out. Again, I can’t get enough air-and I can’t blame the Platypus because I’ve ditched it. To my surprise and horror, despite 30 years of hiking and 15 years of strenuous thrice-weekly aerobics-a program I stepped up considerably in the three months before this trip—I am definitely the weak link on the team. Early in the hike Lisa called with some urgency to take the satellite phone out of the red river bag and transfer to it to my back-pack, which has been given to the 6-year-old again.

The first three hours are the worst-so steep my heart is pounding in my chest like some crazy animal trying to get out. Again, I can’t get enough air-and I can’t blame the Platypus because I’ve ditched it. To my surprise and horror, despite 30 years of hiking and 15 years of strenuous thrice-weekly aerobics-a program I stepped up considerably in the three months before this trip—I am definitely the weak link on the team. Early in the hike Lisa called with some urgency to take the satellite phone out of the red river bag and transfer to it to my back-pack, which has been given to the 6-year-old again.

As I try to pull my body up the 45-degree, muddy slope, a local meri with a skin disease extends a scrofulous hand. I grasp it gratefully. Bugs, sweat, leeches-none of this matters now. All that matters is the next step, and it takes all my strength and all my wit to take it. And then, another, and another.

Each step offers a new opportunity for calamity. Slipping backwards in the greasy mud. Pitching forwards. Crashing through ground that looks solid but is really only sticks covering a hole, like a pitfall trap. Slipping on a slick fallen log that serves as a bridge. I very nearly fell off the actual bridge over the Urua River yesterday-saplings laced near each other with lianas. The bridge had hand rails, but the right rail, which I was holding, actually leaned too far off to the right and then disappeared. I couldn’t see this because I had taken off my glasses-too steamy. Only one person can go over the bridge at a time and it is quite long. People were yelling, trying to tell me to switch rails, but I was too deaf to hear them. Joshua, one of our wonderful dancers from Yawan, appeared behind me and led me safely and gently to the other side. What a gentleman.

There are stinging nettles along the way, which the people call fire plants. Leeches can brush off on you from the leaves’ tips. But we don’t even bother to look for these. “When you hike in New Guinea,” says Lisa, “what you see is the ground.” And this is where you must focus your eyes for every step, looking for the imprints of the bare feet of the porters and meris who are going before us, watching for the place where strong toes squeezed into the mud to achieve that one step. And the next.

Mud of all kinds. Black mud, brown mud, slippery mud, even more slippery mud, skating mud. Even standing still on relatively flat ground I find myself slipping backwards.

The porters hike far ahead. Leading our group is Gosing, Lisa’s favorite auntie. “She’s so strong,” says Lisa, “but she is pacing us.” Gosing is an elder-people only live into their 50s here, dying of emphysema and respiratory infections, the legacy of smoky fires. But in terms of overall fitness-strength, endurance-they leave us Westerners, despite our vitamins and power bars, our Vibram-soled boots and aerobics classes-in the dust. Or the mud.

Except they don’t leave us behind. Gosing turns to encourage Lisa and check on the rest of the group. I am directly behind Lisa. I hope folks have let me keep this position because I can ask questions and take notes on what Lisa says-and not because people suspect I might drop dead. Lisa is doing fine. We joke about a Lisa Dabek Action Figure to go with the book. She gives me a radiant smile at every stop. I smile back but fear that as the day wears on it looks more and more like a chimpanzee fear grin.

Besides Lisa’s friend Gosing, all of us seem to have a personal meri quietly looking after us. When Holly and Christine slip, the meris behind them say “Sorry!” as if the mud is the fault of their poor hostessing. My meri is a girl named Leah, about 14 years old, who amazingly is carrying a half-full Dittyman bag via a string attached to her forehead. She extends her hand to me as we cross especially slippery logs. Without her, I could never cross. I am getting Elvis Leg. Lisa tells us that she lost three toenails on a hike like this two years ago, and a fourth on a subsequent hike-her boots had shrunk too tight sitting by the fire.

All of us are in good spirits, though. Nic bounds ahead, mountain-goat-like, as if his equipment weighs nothing. He likes to lurk ahead, upslope, so that when Lisa rounds a bend he can catch her like the paparazzi stalking Princess Di. Christine and Holly are singing at one point, and Holly’s meris have put orange ginger and red rhododendron flowers in her hair. The air twinkles with the chatter of plum-faced and Papuan lorikeets.

We break after 3 hours at the top of a ridge-where a member of a previous team, a 30-year-old amateur bodybuilder, threw up and confessed he thought he could not go on (He eventually made it, though). We have power bars and chocolate cookies and the aptly named HARDMAN HI-WAY crackers, which are indeed as hard as the highway. They must be popular here because they can’t go stale. Little could happen to make them worse than they already are. We eat them gratefully.

When we look below, the scene is breathtaking. Below us, the exposed slope with its bamboo splayed like fireworks and the people’s gardens, the under story of houseplants like coleus and impatiens. Far in the distance, Joel points out Yawan and Towet. We seem to have climbed an impossible distance. But we are still “longwe” and certainly not “clostu.” Six hours more hiking remains before we can rest-and then three more the next day.

We do it in three-hour increments. The fact that I have not yet died suggests I am not having a heart attack after all, and this is encouraging. The second stage of the hike takes us along a ridge to the Yapum River. Here we find more New Guinea impatiens, coleus-but now, more moss. At 2:30 Lisa points with delight to a raspberry-like plant with no spines. “When you see this,” she says, “you know you’re in tree kangaroo country.”

Everywhere around us now is almost unspeakable beauty. Great trees hung with moss. Tree ferns, the coils or their orange fiddleheads bigger than cabbages. The hike has flattened out somewhat. And then uphill, to where the bulk of the porters are awaiting us: the crossroads, Lisa calls it, between the trail to Yangaron-site of distance sampling-and the trail we’ll take to Wasaunon.

“Can we hike another three hours?” Lisa asks our group. Joel’s cold is in miserable, full bloom. Christine has a cold, too, and is bleeding onto her borrowed shirt from a leech bite on her stomach. I can tell I am going to throw up at some point, but I certainly am not going to mention this, and hopefully this will not happen for another three hours. We all agree enthusiastically to press forward.

Now we are in the most beautiful forest yet-the trees are taller and mossier. There’s a long, difficult downhill. Lisa walks down one difficult step and a moment later hears me grunt and knows I made it, too. We warn each other of hazards ahead: “Hole! Pass it down!” “Really slippery rock.” “These logs are rotten.” “Bad mud.”

At the bottom, at the Kotem River, we can see the men have already put up tarps, beneath which we can pitch our tents. And now it is raining-pouring-and getting dark. I wander off to be sick. As I am throwing up I remember Nic declining a scoop of powdered Gatorade in his water bottle this morning. “Tastes like vomit,” he said. I am thinking, “No, this tastes like vomit.”

25 March-Kotem River to Wasauonon

Morning: get back into wet socks, wet pants, wet shoes. Pack our tents. This hike is only three hours. But most of it is uphill.

Robin points out a tree with hollows like a woodpecker might make. Into these holes the triok pokes a long finger, in order to probe for grubs. We pass a pandamas tree with a musky scent. “Mountain cuscus,” says Lisa-a lovely soft-furred beast with enormous eyes and a curling prehensile tail and a white belly. To smell one—what an intimate sense!-gives me a rush of adrenaline. Which I immediately need.

The slope directly ahead is as steep as the one behind. But it is taking us to Wasauonon, and tree kangaroos-home.

I am now leaning over gasping for breath every five minutes, my walking stick the only thing between me and collapse. My stomach is getting ready for another launch. But I can do anything for three hours.

Porters and meris are coming down the trail now. We pause to shake hands with each one. When we were on the way up, people were coming down from their gardens. “Apinun!” we would say-it sounded like “Happy noon!” Now we say “Tank yu tru” as we bid goodbye to those who carried our food and our tents, our scientific and veterinary supplies, and whose hands and feet lead us over slippery logs and up muddy slopes. Gosing is leaving, too. She went on ahead of us this morning. Lisa gives her a warm hug. Many of the people are carrying plants down with them, some to eat or maybe to use for medicine, some with roots to plant in their gardens.

We come to the first of two fern houses. These are living structures, which look like they were built long, long ago. They are tripods covered with living ferns. We are “clostu” now. More uphill. A second fern house. Then the kunai-a grassy area that also can serve as a helipad, which is how Nic and Lisa and I will be leaving. Tree ferns. Then a 10-minute, very slippery muddy walk-and we’re home.

The men have erected a series of blue tarps on pole tied with vines, beneath which we erect our 9 tents-a tent city. And there are two houses, the walls of logs piled upright, not lengthwise, and between the cracks of which ferns grow. Smoke drifts out the doorway like steam from a dormant volcano. One room is a kitchen with our stores piled on shelves made of sticks lashed with vines; other is a sort of sitting room. There are also two haus pek pek, one for men and one for ladies.

And again, as the rain crashes down, I am sick. But never for a moment frightened. Although my body feels lousy, I feel safe and cared-for. Last night, after I threw up, I apparently went hypothermic and stupid-but Nic went looking for me and stuffed me into first a jacket and then, into Lisa’s tent. Today, as I throw up in the haus pek pek, Toby erects my tent; Holly brings me Imodium and a hug; Nic and Lisa check on me again and again as I lie in the tent. And then Joel comes in and lies beside me and talks to me, until I fall asleep in paradise.

26 March-Wasaunon

“Luxe, calme et volupte”-the line from Apollinaire suits this place perfectly. The ancient trees look like benign wizards, bearded in moss, the moss studded with ferns, the ferns dotted with lichens and liverworts and fungi. Life piles upon life everywhere: there are fruit and flowers where you don’t expect them, and blinding beauty where you expect it even less. Nic disappears into the haus pek pek until I worry he is ill, but he’s photographing a gorgeous fungus growing there.

Everything is clothed in moss, as if the clouds themselves have become vegetal. It’s a place of sweetness and softness and moisture. Moss: the “first mercy of the earth.” It covers the tree trunks, the vines, the ground. It hangs in big clumps from the branches-looking exactly like a tree kangaroo. “And for years,” says Lisa, “this is all we saw.”

But now she knows the home ranges of four animals. Jessie’s-named after her beloved dog-begins perhaps 15 minutes hike from camp. Her joey, Shelby-named after Lisa’s present dog-will probably be nearby. “Shelby could be off on her own now,” says Lisa, “which actually would be totally fascinating.”

They are up in these soft cushions of moss now-and one team of men is already out looking by 8 a.m. “They’re out looking for Jessie now,” says Lisa. “And Janet (named after the field vet last year) might still be with April. Wouldn’t it be cute to see April again?” she asks Joel.

We walk some 15 minutes over muddy slopes to the holding cage, to prepare it for any tree kangaroos the men might catch. The roughly 8′ x 14′ enclosure was built last year entirely out of sapling sized sticks tied with vines. Ferns, moss, lichens and liverworts are growing from its walls already. “It’s actually a living structure, which makes it even nicer for the tree kangaroos,” Lisa says. After a year, it’s still in good shape, but needs some repair. Christine is sent inside to see if the climbing limbs are secure and the walls intact enough that even a joey could not slip through. She and Lisa determine the necessary repairs, and Huck-Finn-like, we begin to amass the materials for our tree kangaroo house. Joel wields the machete to cut ferns to rain-proof the roof. Toby climbs up top to seal the chinks with sticks. Robin strips moss from lianas to tie the sticks in place. “It’s like building a tree house, but even better,” says Lisa, “it’s a tree kangaroo house!” And more fun because we do it all with no hammers or nails.

* * *

The forest looks like a setting for a fairy tale. The tallest trees-Dacrydium, which tree kangaroos prefer-are ancient evergreens called podocarps, which can live to 1,000 years old. The big ones here are probably 600. Among the mist and the moss, the ferns and the orchids, you half expect a troll or a dwarf, an elf or a gnome to appear. But it’s better than that: here live tree kangaroos, pademelons, cuscus, trioks, quolls-animals so beautiful and fantastic that they seem something dreamed up by a plush toy manufacturer on acid.

The forest looks like a setting for a fairy tale. The tallest trees-Dacrydium, which tree kangaroos prefer-are ancient evergreens called podocarps, which can live to 1,000 years old. The big ones here are probably 600. Among the mist and the moss, the ferns and the orchids, you half expect a troll or a dwarf, an elf or a gnome to appear. But it’s better than that: here live tree kangaroos, pademelons, cuscus, trioks, quolls-animals so beautiful and fantastic that they seem something dreamed up by a plush toy manufacturer on acid.

The plants here are astonish and delight. Some are funny; are all beautiful. Some are fit for a doll’s greenhouse. There are micro-orchids only 5 inches long with blooms no bigger than a dress maker’s pin. There are fungi that feel like the rubbery ears of an old man. There are vines that are covered with six species that I can count in a three-inch stretch. Ferns spill down from the trees like green waterfalls. “It’s the dry land equivalent of a coral reef,” says Robin. The tree kangaroos eat over 90 species of plants-more than are usually found in nine square hectares of temperate forest. “Just one square foot is a whole little world,” says Lisa.

“There is nothing so beautiful in all the built world,” I say to Lisa.

“But they are destroying this for the built world,” she replies.

* * *

While we were fixing the enclosure, the men were out looking for TKs.

While we were fixing the enclosure, the men were out looking for TKs.

The five of them began at 6:38-Kuna and Gabriel, Joshua, Nixon and May. They started at the grassy kunai and took the “I” trail that leads to the megapode mound we saw this afternoon. They split into two teams, Gabriel explained to me later, one heading over a ridge and one below-so if one team found a TK it might run into the other’s terrain. “Our eyes are always up in a tree for a tail hanging,” said Gabriel, “or on the ground for pek pek.”

By 7 a.m. Gabriel’s team had found the shoot of a shrub that had been browsed by a TK. At noon, on Trail “D” they found a whole tree covered in scratch marks “like a freeway” said Gabe. But no ‘roo.

That afternoon they were in Jessie’s territory and found all her favorite trees. There was fresh scat, but no ‘roo visible.

What they didn’t know was that Kuna’s team, who split off from the others on the “I” trail, had come upon a TK at 8 a.m. Joshua, to his surprise, came upon one on the ground, standing on its hind legs feeding on a shrub. Seeing Joshua, it took off, hopping on the ground, and disappeared in about two seconds. Kuna saw only the back and the tail. Joshua took off after the roo, and might have caught it-if he hadn’t tripped over a vine, fell over a log, and then got a stick in his gum boots!

“We were so wanting to get our hands on it,” Joshua told me through Kuna. Both men were eager. Kuna has only seen one in captivity. Joshua has seen many. “Planti taim mi lookim,” he said-the last time 3 years ago in 2002. They got photos but never caught it, downstream from where we camped on the Kotem River.

“I am happy I saw it,” he said of this one, “and grateful to share it with you. We hope we see more. It’s still out there.”

* * *

At night: spotlighting with Robin and Toby. Near camp, we hear the loud, zippery “WOW-WOW-WOW” call of the mountain cuscus. We walk out of the cage where Robin noted a tree about to fruit. The fruit, the porters had told him, was “Kai kai lik lik black bokkus”-food of the smaller ‘black box’ fruit bat, or blossom bat. Sure enough, the orange seeds have been taken, and in their place, wet, fresh pek pek that smells much like the fruit. We all discuss and smell the bat excrement in the dark, and then venture to the kunai to bathe in the moonlight. We spot the Southern Cross, find the Big Dipper upside down, and watch Orion on his belly diving beneath the horizon as the Earth spins. Toby saw a shooting star tonight and made a wish, but he won’t tell.

Easter Sunday

“They’ve got one!”

“They’ve got one!”

When we heard the news, we all hugged each other and leapt with excitement. We raced down the muddy trail over the slippery logs, past the big dangerous hole and up and down the slope to the Tree Kangaroo House.

“It’s a healthy young male!” Gabriel announced, holding a bulging burlap bag that once held coffee beans. Today it holds a 7.8 kilo tree kangaroo that the trackers have named Ombom, the Tok Ples word in Towet for the clumps of moss that so resemble TKs.

Ten people went searching this morning, assembling at 6:38 (as Gabriel precisely recorded) at the kunai to comb the same area that yielded Joshua’s sighting yesterday. Walking almost abreast like an advancing army, they swept over the hill, moving a a group within hearing distance of one another. For more than an hour, they saw nothing, Gabriel told me-but then at 8:25 Wewas spotted the TK about 12 meters up in a Euodia tree and called to the others. The animal was calmly perched in the crotch of a tree, looking down at the men below. “He was just looking at us and huffing, and looking very beautiful,” Gabriel said. The trackers began to build the im, and once it was completed Wewas began to climb the tree, about 8:40. The TK went out on a small branch, and leapt-at first with front legs extended, but landing on his back. Boas jumped on top of him and tried to hold his head still-he bit him on the finger. May held both legs; Joshua went for both arms. They held him still for four minutes while Gabe came with the bag and lowered him in by the tail.

So now Lisa kneels beside the bag as Toby and Joel weigh it. Huffing sounds issue from the bulge in the burlap. We are all breathless with excitement as the small logs that serve as the cage door are removed and Gabriel releases the creature from the bag. He doesn’t come out very quickly. We peer between the sticks of the cage into the shade and see-to our horror-that his left lag is dragging.”

“Oh shit, man,” says Robin. “It’s broken.”

But it may not be broken. It could be a nerve injury. It could be a dislocation. The worst thing is we can’t find out until Holly examines him under anesthesia-and she can’t do that until the missing veterinary bags come up from Towet. How they got left behind is somewhat of a mystery, as is why they didn’t come up as soon as we noticed they hadn’t made it, which was the night we arrived. Lisa was livid, and sent people down yesterday, and again this morning, to see where the bags were and make sure they came up. They are essential-we can’t do a thing without them.

Holly tries to assess the injury from talking with the trackers. Was the animal already injured, causing him to fall? Was his struggling with all limbs on the ground? No one gives a definitive answer. It is such an adrenalized, heart-pounding moment when you are catching a wild animal.

So we wait for the bags, back at camp.

11:15: The vet bag is here! Holly, Lisa, everyone-we’re overjoyed. We begin to unpack it. But alas, it is only one of TWO veterinary bags, and the anesthesia kit isn’t in it. We sort through supplies and take them to the kunai to wait for more porters.

12:15: “They’ve crossed the river Kotem! They’re on their way!” Gabriel reports. Meanwhile we go over our jobs: Gabriel will take measurements of the roo and Joel will record them on the data sheets. Chris will restrain the animal and act as vet assistant. Lisa will help with anesthesia-when it comes.

Meanwhile-poor dear Ombom. We’re frustrated and helpless. We speak in low voices, even though Ombom is far away. “Worst care scenario is a fracture,” holly says to my surprise. “If it’s a nerve we can get the swelling to go down.” But even if it’s a fracture, it’s possible it could heal in 2-3 weeks, if we can keep him fairly immobile.

“We’ll do the physical exam first,” she says.

1:35: “More bag coming!” five more porters appear. We open the bags: data sheets, camp chairs, and Easter treats-but no anesthetic. And now it looks like rain.

1:50: The last bags appear. Dugs, ace bandages, and the isofluorine. “It’s Christmas!” cries Holly, opening each package with joy. “I hope I can help.”

At 2:10, Holly, Christine, Gabriel and Joshua approach the cage. The temperature is dropping fast: 21.4 C, 20.1, 19-and the humidity rising-50 %, 56%, 60% in the first five minutes of readings. The first drops of rain start as they fit the anesthesia cone over Ombom’s sweet pink nose and lay him on a space blanket o the ground. His color is spectacular. His tail is golden, his back a deep red chestnut, like a topaz. His belly is lemon yellow. He is the color of a rainforest orchid. As he lies here before us so vulnerable, we crave only to protect him-and yet we might be the ones responsible for the injury. Every one of us feels absolutely terrible-far worse than we would feel if one of us were injured. We volunteered for this project. Ombom didn’t.

The team takes the measurements: Tail 54.5 cm. Temp 96.7 F. Body 50.05 cm.

Christine holds the face mask over the roo. We can’t help touching him. His fur is softer than velvet, like a cloud.

“He doesn’t seem to have a major fracture,” says Holly as she palpates his muscles and moves his bones. “And he didn’t go without breakfast!” feeling his full tummy.

She gives him a shot of dex in both thighs to reduce the swelling around the nerves.

As Holly works, the porters gather ferns to make a soft springy bed for him in the smallest part of the cage. The rain is falling harder now and two umbrellas shelter the prostrate animal.

“He’s doing great,” says Lisa. “His breathing is even.”

They microchip and collar him, give a vitamin and mineral shot.

“There’s a good bed of ferns?” Lisa asks.

“Yes, yes,” says Gabe.

At 3:10 he’s waking up.

“I don’t know he’s going to be OK,” Holly says tentatively, “but we have a good prognosis.”

* * *

“I’m always torn up about this,” says Lisa. “You don’t know what’s going to happen. You hate to think we might hurt an animal. But I have to think of the big picture. We are here to protect the habitat for all the tree kangaroos. We want to protect all of them-and this animal is helping us do that.

“Oh, I hope he’s going to be OK.”

29 March

It feels like a day of forgiveness. I woke up in Joel’s tent after the warmest night for me yet. I had stood outside it the night before listening to him breathe and was so frightened it might stop that I got my sleeping bag, crawled inside and slept next to him. He has been so brave and strong. Mercifully his headache is receding.

It feels like a day of forgiveness. I woke up in Joel’s tent after the warmest night for me yet. I had stood outside it the night before listening to him breathe and was so frightened it might stop that I got my sleeping bag, crawled inside and slept next to him. He has been so brave and strong. Mercifully his headache is receding.

We all spend the morning doing humble chores: Christine and Holly check on Ombom-he’s still limping, but he’s eating, and seems to be otherwise fine. We are washing dishes, making soup-just Miso and noodles from a packet, but so warming and delicious! I am carving salt and sharking down my food-a bowl of soup and rice wafers drenched in soy sauce.

Robin is determined to paint the fuchsia flowers of an aerial rhododendron-he falls 12 feet-but thank God he’s all right. Later, with Toby spotting him, he retrieves the branch. Nic is photographing a butterfly. The men have gone to find tree roos-we agree the top priority is the animal’s health.

At about 11, a miracle: the men come back bearing a long-beaked echidna! Endemic to New Guinea, it is a Dr. Suess character come to life: a fat, funny, tribble body with only a few spines; dear, tiny black eyes; black feet that appear to be on backwards, and a six inch long tubular snout that is so long he literally trips on it as he trundles along.

The trackers came across his multi-tunneled burrow and debated whether to leave him and continue the TK search or bring him back to us. We are so glad they chose the latter. Everyone is thrilled-but also very wary of stressing him-while desperately wanting to VDO and photograph this extremely rare animal that none of us would ever have a chance to glimpse anywhere else on Earth for the rest of our lives.

For such a harmless, hapless looking character, the long-beaked echidna is surprisingly big-this one is young, but as an adult will weigh as much as a young tree kangaroo-and strong-he tears a hole through our table by parting the lashed-together sticks with his hands. He stabs his long nose into the earth and it passes through the soil like it’s water. And he walks through the wall of the cookhouse like he’s Caspar the Friendly Ghost.

“They’re the neatest animals!” says Lisa. “Can you imagine it burrowing between your toes?”

I touched his back and found the charcoal-colored fur surprisingly soft. He is much furrier than the short-beaked, an adaptation to the cold of the cloud forest. His ivory-colored spines are few but quite sharp-the fellow who caught him was cut by a spine that sliced painfully through the nail bed of his thumb. Yet he smiled as Holly treated the wound. The young fellow was quite obviously delighted that his find would elicit such wonder from the foreigners.

The animal was found not far from here. After we had photographed and videoed him for perhaps 10 minutes, he is returned to the coffee bag and taken back home, we hope no worse for wear.

It seems only minutes have elapsed since his visit when at 12:10 another team of trackers arrives bearing a mountain cuscus! He is a plump, furry fellow-dark except for his moon-white belly and pink, grasping hands and the naked lower half of his grasping tail. He sits on a moss-covered tree-mortified to be facing Nic’s flash and looking terrified-until finally he bravely threatens Nic with an open-mouthed hiss, and the shoot is off. He’s released up a tree-a tall one with no lower branches. He had been sleeping when the men climbed the tree and took him away.

This place is full of such unlikely animals, with incredible bodies and fantastic names. Pademelons have dug holes in the kunai grass the men saw a dorcopsis and baby under a tree the other day. We visited the mound where the brush fowl-a megapode-was using the heat generated by compost to incubate his eggs (the male tends them, adjusting the temperature as needed, cooling by digging holes). The nest is the size of a Volkswagon. Quolls live in the brush. We don’t see them all, but we can find their nests, hides and holes. “You get a sense of all the animals who live here,” says Lisa. “The place is full of little beds.”

* * *

3 p.m. and it’s raining like the Devil. Some of us are huddled by the smoky fire-our hair covered in white ash, the smell of smoke and human body oils hanging in our filthy clothes. At least my clothes are filthy; nothing I’ve washed has ever dried except two pairs of underwear, which I surreptitiously cooked over the fire when the men were out searching for TKs. It is always cool and wet at night, and I sleep in all my clothes except my raincoat, my pants and my socks-the latter because of the mud and also the bush mites-if they get into your sleeping bag, there is no recourse, said Lisa. I even sleep with my headlamp around my neck. And still I am cold. Morning and evening, you can see your breath.

3 p.m. and it’s raining like the Devil. Some of us are huddled by the smoky fire-our hair covered in white ash, the smell of smoke and human body oils hanging in our filthy clothes. At least my clothes are filthy; nothing I’ve washed has ever dried except two pairs of underwear, which I surreptitiously cooked over the fire when the men were out searching for TKs. It is always cool and wet at night, and I sleep in all my clothes except my raincoat, my pants and my socks-the latter because of the mud and also the bush mites-if they get into your sleeping bag, there is no recourse, said Lisa. I even sleep with my headlamp around my neck. And still I am cold. Morning and evening, you can see your breath.

The only parts of my body that I have seen since leaving Lae are my hands and my ankles, and neither are a pretty sight. The ankles caused quite a stir when we were all in Joel’s tent after dinner the other night, and took off our shoes and socks. They’re covered in red chigger bites which are swollen and infected. I could have chiggers and ticks, leeches and bush mites all over my torso, my upper arms, my neck-I wouldn’t know. I haven’t seen them. Christine bled for hours from the leech bite she got on the hike up, but only noticed it because the blood had seeped through her shirt-or rather, someone else’s shirt. Only today did we learn, via sat phone, that one of her two bags lost in transit finally made it to the Melanesian hotel. Everyone is lending her their stuff.

Occasionally I wonder about my face and hair. My face has some weird bumps on it, but I don’t know what they are. My hair seems to be all over the place. I am glad there are no mirrors in camp. We all see ourselves mirrored in the faces of our friends-which light up when we are coming.

Some mornings when we wake someone asks, “Did you feel the earthquake?” A few times I’ve felt the trembles-like a heavy person is walking by in a house with an unsteady floor. The Earth feels so new here-no wonder we can sometimes feel its molten, beating heart.

30 March

Yesterday it rained half the day and all of the night, but today we have no rain at all, and sun enough to dry the clothes that have hung, sopping, on our clothes lines under the blue tarp since we arrived-and dry our hair. The big event we planned for this day was we 4 ladies washing our hair in the freezing waterfall. Nic was documenting Lisa’s toilette. It would have been torture-“Hold it! One more time! Can you hold your head in the water again?”-were it not for my brainstorm we carry a kettle of boiled water down with us. But even so-Cripes, it was freezing! The water was so cold it felt like a headache, like a snowball down your shirt, like a doctor freezing off a wart-just awful! My feet turned to blue blocks of ice. But the camaraderie was splendid. And Christine, who with her nearly waist-length blonde hair forsook the comfort of the kettle-water-took a time-delay photo of the wet heads.

About to bathe in the waterfall, Lisa commented “Fortunately I am a member of the Polar Bear Club.”-a group of about 200 Rhode Islanders who plunge into the freezing water of Naragansett Bay each January 1, a stunt to raise money for the Rhode Island Special Olympics. “It prepares me for the field!”

31 March

Today the men are searching for TKs far from camp, hoping that even if they do not find one, they might drive them closer to us. But Lisa, Gabriel, Joel and Toby decide to look on their own, and take me and Nic along.

It is a sort of pilgrimage. They are taking us up the steep “B” trail, a loop that climbs to a ridge from which you can see the faraway blue peaks of the Sarawoged Range, of which we are a part. It’s an exceptionally beautiful trail but also one of the most remarkable, because it was here they had first captured and then released and relocated Jesse and Shelby, the first wild TKs in history to share the secrets of their daily movements, activities and home range.

Along the walk, Gabriel names some of the plants for us. Dacrydium of course are the tallest trees, the ones in which tree roos prefer to rest. But actually he says, white TKs may find foods in the tee tops-orchids, for instance, are found in their dung-they do a great deal of feeding on the ground. They eat a lot of Elastostema, the raspberry-like plant Lisa IDed as one of the indicators of TK country. Once again I am struck by how benign everything is: the raspberry like plants, instead of spines, have soft moss coating the stems, and if you break the stem, its center is soft and watery. Elastostema is found only in this province, Gabriel tells us, and its family name is Morobensis.

The forest floor here is dotted with the white flowers we’ve seen elsewhere, like small dogwood blossoms but with more petals and golden centers. The ttee that owns them is called Sauraria, and Gabriel says TK’s love to eat the shoots. It’s as if a wedding party has just been through, leaving the path strewn with these flowers.

This area of forest seems to me particularly friendly and accommodating, with some areas just like the rooms of a house: here a log covered with moss looks like a couch upholstered in green velvet, with stumps as footstools and easy chairs, and even fluffier moss as carpeting. The vines snaking up the trees look like banisters for a tree kangaroo staircase. Looking 90 feet up into the trees, into the clumps of cushiony moss, Lisa says, “Those tree kangaroos have it right-sitting up in their mossy beds, on top of the world!

“Oh, it’s so nice to be up here!” she continues, remembering the delight of the first successful capture. “It was such a momentous day!”

The men had been standing on a ridge when they saw her. Earlier, James told me though Gabriel how after a series of hugely frustrating days, Dono and he had teamed up that day. “This is our land-why aren’t we seeing any tree roos?” they asked one another. Dono sat, tired, and James leaned against a tree. And when James looked up into the moss, he saw a tree kangaroo running over a branch. Dono watched the animal while James ran into camp to get Lisa and her assistant, Stacey. Lisa was so excited she left the VDO tape behind. That was Jesse-who had a female joey, Shelby.

And here is that very tree-a towering Dacrydium, at the base of which three inch diameter white impatiens bloom. “Here’s where Jesse dropped to,” Lisa shows us-onto soft, springy, harmless ground. “She launched off and sort of glided down.” Dono was petting her to calm her down.

Joel and Gabriel next take us to the highest point in Wasauonon: GPS says 3058 meters-about 10,000 feet. We look around at this vast area. Besides Lisa’s team, almost certainly, no foreigners have ever set foot here.

“When you look in these trees,” says Lisa, “you can easily imagine a tree kangaroo. You have the feeling they’re watching you. I’m sure there’s a tree kangaroo here!”

So we search the tree trunks for scratch marks. Here’s one-but the scat beneath the tree belongs to a mountain rat-more curved, like macaroni. In her previous studies, Lisa found that pek pek was the most reliable indicator of a TKs presence, and also the best way to gauge the population. Before collaring the tree kangaroos for the first time last year, the only way to learn about them was to guess at their population densities by distance sampling-counting the pek pek at predetermined intervals. The freshest pek pek has an olive sheen. But we don’t find any today.

Even with the radio collars, the TK still hide many secrets. Joel recorded observations on a data sheet, using binoculars and GPS data. “If you see them, most of the time they’re just watching you,” he said. You don’t get to see much behavior. Sometimes you don’t even get to see the whole animal. “You might see a tail, or an ear, or a nose. Sometimes you don’t see them at all, but you know they’re in the tree because of the radio telemetry.”

But this data is hugely important: fro these telemetry readings, the scientists will be able to gauge home range, as well as determine which trees the roos use-“and this is how we’ll know what habitat needs to be protected,” Lisa says.

“Gabriel and Joel proved everybody wrong,” she says. “People said it would never work to get the signals from the collars. They would bounce off the trees. But we did it-and this is just the start.”

The data from the 3 females is thrilling. But we have yet to collar a male.

April 1

From the moment we woke, Lisa felt this would be a good day. We both like to be up to see the men leave on their search-to wish them well, to send our gratitude with them into the forest. We saw may leaving and were glad he was feeling better. He has had malaria, and it has been terrible to see this strong, serious elder crumpled by the fire every morning since it struck. He must feel terrible. Holly is trying to treat him, but this is very worrisome.

Lisa was washing clothes and I was doing the dishes down by the stream when we got the word at 8:35: “Tree roos! Two of them!” It must be mother and a baby-and Nixon says they are both still in the tree, “clostu” here-we race after him.

Nic dashes for his photo equipment. Robin follows with the video. But no one waited for us. “Where are they? Can we find the place?” The party disappeared ahead of us. I can hear their voices trailing after them across the kunai.

We’re frantic-all of us. Nic, Robin and I wait at the kunai, hoping the party will send someone back to lead us. They know we need these photos and this story for the book, and Robin needs the video for the project—these are images and moments that can’t be recreated later. We must be there. But no one comes. “They said just across the kunai,” I remember. We try to track them, and find an arrow made of sticks pointing off the “I” trail. We follow this, Nic calling loudly-but no answer.

We circle back to the kunai. As it turns out, Victor ran all the way back to camp searching for us. When he finds us, we all run. I am gasping for breath, my heart pounding, my chest feels like it will explode. It seems I can feel the arteries in my heart, the faulty mitral valve slamming and buckling, the backwash of blood. Robin takes my pack-even my fleece, tied around my waist, and my fanny pack with my notebook and pen. And still I struggle. While the two men race ahead of me like antelopes, I am falling, crashing through the trackless bush, slipping over logs, falling onto the spike cut stems of baby trees, sliding through the mud, whacked in the face with foliage, my feet tied up in vines. Nic is way ahead of me, and now I think I could lose him. Strong, tall, chivalrous Robin takes pity on me; he plucks me out of holes as easily as a farmer pulls up a turnip. We are crashing through a screen of vegetation. Will the tree kangaroos still be there?

At 9:40 we reach the site. We can see one roo at about 25 m up, looking almost like a red panda, looking down at us with ears priced forward, intent but not appearing panicked. Her long golden tail hangs down from a Sauraria tree.

“I can’t believe it,” Lisa says.

And more amazing, in an adjacent tree-another tail-her offspring.

“Bigpella pikinini,” the men remark-a very, very large kangaroo for a youngster, surely nearly grown.

“This is incredible! This is amazing!” Lisa says. “The whole field season is riding on these moments. And I was thinking as I was running how much of a team we are-this is what it means to be a team. We depend on these men. If not for them, we couldn’t be here doing this. And if not for us-they wouldn’t be doing this, either.”

* * *

The men had left camp that day optimistic. May, in particular, was confident. Gabriel had suggested May stay back, since he’d been sick with chills and joint pain and headache, typical of malaria. But May felt this would be a lucky day.

“It was sunny and warn-a good day for the tree rooms to come out and warm themselves,” said Gabriel. “For the first three days we had been traveling more than one kilometer to find tree roos. I wanted our presence to drive them closer to camp. So we decided today to try closer, on the “I” trail-and it worked.

“All of us spread out. Victor was looking in particular for Schefflera plants-an epiphyte TKs love-the underside is brown and the top green, and he spotted some in a tree. But no roo. He then scanned an adjoining tree-and there it was in the Sauraria!” It was 8:18 a.m.

“Immediately,” Victor told me through Gabriel, “I barked like a dog, to keep her up in the tree. And the sound called the others. Everyone ran and admired the roo-and after two minutes, May noticed the other tail! Then they sent Nixon back, and started building the im.

* * *

“This is the miracle of doing work here,” said Lisa as we stared through binoculars at the female. “They are so elusive. And then, you finally find them.”

We photo and video and stare through binoculars till 10 a.m. Now to get the animals down. Victor climbs a smaller tree adjacent to the female’s Suraria. Within two minutes he is 25 meters up.

“Joel-do you see where she is,” Lisa asks. Joel has eyes like an eagle.

He does, and points. The female climbs another 10 meters up, wary of Victor. We are horrified-now she would have a 35 meter drop. Suddenly, she leaps-she falls 20 meters—she grabs a smaller tree-and begins to back down. The men close in around her. She has almost touched ground when May grabs her tail.

“Pikinini! Pikinini!” the men call out next-the other roo is 20 meters up in a Decasperum tree and not moving. Victor, still up the adjacent tree, begins to throw sticks at the youngster-and he drops, tail first, catches a vine in his hands, turns himself around head first and lands on his front paws. Boas pins his body, while May holds his feet and Joel holds his arms.

It is only now they see the “baby” is really an adult male. What a dreadful date! Both TKs are in burlap bags by 10:10. “Meri na man” they say as they walk back to camp-which turns out to be a mere 850 meters away.

“What a morning!” Twenty five minutes later we are back at camp where Holly and Christine have set up the exam table, the medical supplies and sample vials, the measuring tools and data sheets. A silver space blanket and a grey foam pad are laid out to accommodate each roos body once anesthetized.

First they are weighed, and Joel notes the temp and humidity.

“Let’s measure the male’s neck to make sure the large GPS collar will fit on him,” says Lisa. “Let’s do the female first.”

“With the female, we’ll have the same priorities,” says Holly: “Measure the neck. Radio collar. Avid chicp. Grab fur. Check pouch. Then decide whether to take blood.

“Christine will call out pulse and respiration every five minutes. Are there any questions? Is everybody ready?”

“Do you have the collar? The screwdriver?” asks Lisa.

“Yes, yes,” says Gabe, holding the squirming bag on his lap. “We’re ready.”

He dons the big orange leather gloves-exactly the color of the Matchie’s tail.

“Wait-wait-come here!” Gabe says to the squirming bag. “Hold ’em!” he says to Joshua and Gawa. And soon a pink nose pokes through a hole in the bag.

It’s 10:55 and Holly places the mask on the nose. A hand comes out the hole. But within 45 seconds, she relaxes.

“Take her down to 1, please,” she says to Christine, who’s working the anesthetic.

“Let’s lay her on her right side,” says Holly. “Thermometer?”

“She’s moving! Somebody grab her back legs!”

“Three minutes,” calls out Lisa.

“Respiration is 32,” says Christine.

Holly leans forward to listen to her stethoscope. “Heart rate is 16 x 12-you do the math,” she says to Joel.

Gabriel is putting on the collar. “Remember to stretch,” says Lisa-to make sure the collar is snug. Ombom managed to remove his the first night. She’s injected with a microchip, #029-274-864.

“I’m going to do a pouch check,” Holly announces.

“Respiration is 20,” says Christine.

“Tail length is 51,” Gabriel tells Joel.

“Pouch is empty,” says Holly. “Now for the vitamin-mineral shot.”

“This is it,” says Lisa. Holly removes the face mask and checks her teeth. Robin and Toby snap pictures of her face. She’s coming to-it’s 11:06.

“Put her in the bag,” says Lisa. “Tail first, so she can sit. Oh, she’s so beautiful!”

Christine peers into the bag. “She’s blinking her eyes!”

“She was perfect,” says Lisa. “No parasites. The left ear was the only one I checked.”

“Uh-oh,” says Christine. “She’s got her hand up by her collar.”

“She’s taking her collar off,” says Gabriel.

Should we subject her to anesthetic again? Toby suggests we try to collar her while she’s in the bag and still sleepy. “We can do that,” says Holly, “but there is always the risk of capture myopathy.”

“Oh, wait!” says Gabriel, peering inside the bag. “The collar is back on.”

We let her rest in Stephen’s lap beneath a tree-and prepare for the male.

* * *

11:20: “Anesthetic machine-gas ready-radio collar,” says Holly, “And she’s OK?”

“OK-we’re ready.”

Gabriel unties the top of the male’s bag. Immediately the burlap begins to boil with movement.

“He’s doing somersaults in the bag!” Gabriel says. It’s all he, Joshua and tracker Joel can do to hold him.

The male grabs a glove through the burlap-and pulls it off. He bites Joel on the finger. Now four men are struggling with the wiggling bag. “I’m trying-I’ve got his head here,” says Gabriel. “But I can’t get it out. But the nose is here.”

11:27: Holly places the mask on the bag.

“Oh, he’s very tough,” says Gabriel. The roo doesn’t seem to be relaxing though the gas is on its highest setting.

“Be ready to open the bag,” says Holly.

“Thirty seconds,” calls Lisa. Usually it takes 45 for the gas to take effect.

“Call me one minute please,” says Holly.

“I have his head.”

The bag is off the head. At 11:30 he is taken from the bag and laid on the table.

“Down to one,” Holly tells Christine.

“17 by 12 is heart rate,” she tells Joel. “Here’s the collar.”

“Respiration is 20,” says Holly. “Now we go for the thermometer. I’m putting in the Avid chip, then we go for the hair.”

“Temp: 97.1 she tells Joel.

“Respiration slowing to under 16” Christine warns.

“Respiration’s back up,” she says almost immediately.

“99.2 left hind foot,” Gabriel tells Joel.

Lisa plucks a hair sample and stuffs it in a tube of ethanol for the DNA study.

“He’s under 16,” says Holly-the cutoff for safe respiration rate. “Let’s pull the mask off.”

We all hold our breath, praying he will catch his. “he’s breathing fine,” says Holly.

“Face picture, Robin?”

He snaps it. “Fantastic,” he says.

It’s 11:37. “He’s twitching. His ears are twitching. Let’s get him back in the bag,” says Holly.

“Ten minutes. That was great,” says Lisa, “Oh, great work!”

The female has fully recovered now-from the hole in the bag periodically pokes a pink nose, a clawed hand, an ear. What are their names? Lisa already knows. The female is Tess, named after the border collie love of my life, whom Lisa met when she came to visit last summer. Tess died last previous fall. I wear her ashes in a bracelet my friend Gretchen gave to me. The male is named Christopher, named after a great Buddha master who lived among us for 14 years is our barn, another great soul, also black and white, who happened to be a pig.

* * *

Noon. We’re at the cage. The men have cut fern fronds and line the two apartments with this soft moist floor, and screened the partition between them and the injured Ombom. He now looks alert and cheerful. Markedly better than the day we caught him.

We sit quietly whole one of the men removes the six sticks that serve as the door to the little house where the newly collared captives will recover overnight before their release. Tess climbs out of the bag and scurries up the perch in the cage, from where she regards us intently. Christopher is next door, and he, too, immediately goes for the highest perch

Joel and Gabriel dial up the animals’ channels to make sure the collars are working. 151.080 is Tess’ channel. The beeps are steady. The male’s GPS collar-channel 150.050-gives a different series of beeps, rapid and high pitched. Both are working.

The crew is elated. Victor wants to go out and hunt more TKS-“but the hotel is full,” says Lisa. “There’s nowhere to put more!”

We all shake hands, hug, look into each others’ faces-everyone is beaming with a mixture of excitement, exhaustion and relief.

“The first ever collared male Matschie’s!” says Gabe. “History!”

April 2

Nic and I up early and out to photo the release. No way do we want to be left behind again. But Lisa makes special provisions for us to get there ahead of everyone else so Nic can set up. Nixon leads us along the trail and we are at the site at 9.

I couldn’t sleep all night. During the rain-70 mm yesterday!-I wanted to give my raincoat to spread over Tess and Chris’ cage.