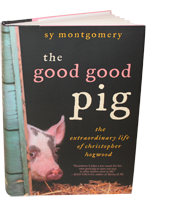

The Good Good Pig

Ballantine/Random House, 2006

Chapter 1: Runthood

Christopher Hogwood came home on my lap in a shoebox.

On a rain-drenched April evening, so cold the frogs were silent, so gray we could hardly see our barn, my husband drove our rusting Subaru over mud roads sodden with melted snow. Pig manure caked on our boots. The smell of a sick animal hung heavy in our clothes.

It did not seem an auspicious time to make the life-changing choice of adopting a pig.

That whole spring, in fact, had been terrible. My father, an Army General, a hero I so adored I had confessed in Sunday School I loved him more than Jesus, was dying painfully, gruesomely of lung cancer. He had survived the Bataan Death March. He had survived three years of Japanese prison camps. In the last months of my father’s life, my glamorous, slender mother-still as crazy about him as the day they’d met forty years before—resisted getting a chair lift, a wheelchair, a hospice nurse. She believed he could survive anything. But he could not survive this.

The only child, I had flown back and forth from New Hampshire to Virginia to be with my parents whenever I could. I would return to New Hampshire from these wrenching trips to try to finish my first book. It was a tribute to my heroines, primatologists Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birute Galdikas. The research had been challenging: I had been charged by an angry silverback gorilla in Zaire, stood up by Jane Goodall in Tanzania, undressed by an orangutan in Borneo, and accosted for money by a gun-toting guard 10,000 feet up the side of a volcano in Rwanda. Now I was on a tight deadline, and the words wouldn’t come.

My husband, who writes on American history and place-making, was in the heat of writing his second book. In the Memory House is about time and change in New England, set largely in our corner of the world. But it looked like it might not stay ours for long. For the past three years, ever since our marriage, we had lived, first as renters, then as caretakers, in an idyllic, 110-year-old white clapboarded farmhouse on eight acres in southern New Hampshire, near mountains Thoreau had climbed. Ours was the newest house in our small neighborhood. Though our neighbors owned the 200-year-old “antiques” that realtors praised, this place had everything I’d ever wanted: a fenced pasture, a wooded brook, a three-level barn and 40-year-old lilacs framing the front door. But it was about to be sold out from under us. Our landlords, writer-artist friends our age whose parents had bankrolled the house, had moved to Paris, and didn’t plan to come back. We were desperate to buy the place. But because we were both freelance writers, our income was deemed too erratic to merit the mortgage.

It seemed I was about to lose my father, my book and my home.

But for Christopher Hogwood, the spring had been more terrible yet.

He had been born in mid-February, on a farm owned by George and Mary Iselin in the town of Marlborough, about a 35 minute drive from our house. My best friend, Gretchen Vogel, had been eager to introduce us, knowing what we had in common. “You’ll love them,” Gretchen had assured me. “They have pigs!”

In fact, George had been raising pigs longer than Mary had known him. “If you’re a farmer, or a hippie,” George had reasoned, “you can make money raising pigs.” George and Mary were quintessential hippie farmers: Born, as we were, in the late 50s, they lived the ideals of the late 60s and 70s—peace, joy and love-and, both blessed with radiant blue eyes, blonde hair and good looks, always looked like they had just woken up, refreshed, from sleeping in a pile of leaves somewhere, perhaps with elves in attendance. They were dedicated back-to-the-landers who lived out of the garden and made their own mayonnaise out of eggs from their free-range hens. They were idealistic, but resourceful, too: It did not escape them that there are vast quantities of free pig food out there-from bakeries, school cafeterias, grocery stores, factory outlets. George and Mary would get a call to come pick up 40 pounds of potato chips or a truckload of Twinkies. To their dismay, they discovered their kids, raised on homemade, organic meals, would sometimes sneak down to the barn at 4 a.m. and eat the junk food they got for the pigs. (“We found out because in the morning we’d find these chocolate rings around their mouths,” Mary told me.)

On their shaggy, overgrown 165 acres, they cut their own firewood, hayed the fields, grew most of their groceries in the garden and raised not only pigs, but draft horses, rabbits, ducks, chickens, goats, sheep and children. But the pigs, I suspect, were George’s favorites. And they were mine, too.

We visited them every spring. We didn’t get to see George and Mary often—our schedules and lifestyles were so different-but the baby pigs ensured we never lost touch. The last time we’d come was the previous March, at the close of sugaring season, when George was out boiling sap from their sugar maples. March in New Hampshire is the dawn of Mud Season, and the place looked particularly disheveled. Rusting farm machinery sat stalled, in various states of repair and disrepair, among the mud and wire fencing and melting snow. Colorful, fraying laundry was strung across the front porch like Tibetan prayer flags. Inside the house, an old cape in desperate need of paint, the floors were coming up and the ceilings were coming down. Late that morning, in the kitchen, steamy from the kettle boiling on the wood stove, we found a seemingly uncountable number of small children in flannel pajamas-their three kids plus a number of cousins and visiting friends—sprawled across plates of unfinished pancakes or crawling stickily across the floor. The sink was piled with dirty dishes. As Mary reached for a mug from the pile, she mentioned everyone was just getting over the flu. Would we like a cup of tea?

No thanks, Howard and I answered hastily-but we would like to see the pigs again.

The barn was not Norman Rockwell. It was more like Norman Rockwell meets Edward Hopper. The siding was ancient, the sills rotting, the interior cavernous and furry with cobwebs. We loved it. We would peer over the tall stall doors, our eyes adjusting to the gloom, and find the stalls with piglets in residence. Once we located a family, we would climb in and play with them.

On some farms, this would be a dangerous proposition. Sows can weigh over 500 pounds, and can snap if they feel their piglets are threatened. The massive jaws can effortlessly crush a peach pit, or a kneecap. The canines strop each other razor-sharp. And for good reason: in the wild, pigs need to be strong and brave. In his hunting days in Brazil, President Theodore Roosevelt once saw a jaguar dismembered by white-lipped peccaries. Although pigs are generally good natured, more people are killed each year by pigs than by sharks. (Which should be no surprise-how often do you get to see a shark?) Pigs raised on crowded factory farms, tortured into insanity, have been known to eat anything that falls into the pigpen, including the occasional child whose parents are foolish enough to let their kid wander into such a place unsupervised. Feral pigs (of whom there are about a million running around the U.S. alone) can kill adult humans who get in their way in the forest. That pigs occasionally eat people has always stuck me as only fair, considering the far vaster number of pigs eaten by humans.

But George’s sows were all sweethearts. When we entered a stall, the sow, lying on her side to facilitate nursing, would usually raise her giant, 150-pound head, cast us a benign glance from one intelligent, lash-fringed eye, flex her wondrous, wet nose disk to capture our scent, and utter a grunt of greeting. The piglets were adorable miniatures of their behemoth parents-some pink, some black, some red, some spotted, and some with handsome racing stripes, like baby wild boars, looking like very large chipmunks. At first the piglets seemed unsure whether they should eat us or run away. Then they would rush at us in a herd, squealing, then race back on tiny, high-heeled hooves to their giant, supine mother for another tug on her milky teats. And then they would charge forth again, growing bold enough to chew on shoes or untie laces. Many of the folks who bought a pig from George would later make of point of telling him what a great pig it was. Even though the babies were almost all destined for the freezer, the folks who bought them seldom mentioned what these pigs tasted like as hams or chops or sausage. No, the people would always comment that George’s were particularly nice pigs.

The year Chris was born was a record one for piglets. Because we were beset and frantic, we didn’t visit the barn that February or March. But that year, unknown to us, George and Mary had 20 sows-more than ever before-and almost all of them had record litters.

“Usually a sow doesn’t want to raise more than 10 piglets,” as Mary explained to me later. “Usually a sow has 10 good working teats.” (They actually have 12, but only 10 are usually in good working order.) When a sow has more than 10 piglets, somebody is going to lose out-and that somebody is the runt.

A runt is distinguished not only by its small size and helpless predicament. Unless pulled from the litter and nursed by people, a runt is usually doomed, for it is are a threat to the entire pig family. “A runt will make this awful sound-NYNH! NYNH! NYNH!” Mary told me: “It’s just awful. It would attract predators. So the sow’s response is often to bite the runt in half, to stop the noise. But sometimes she can’t tell who’s doing it. She might bite a healthy one, or trample some of the others trying to get to the runt. It isn’t her fault, and you can’t blame her. It screws up the whole litter.”

Every year on the farm, there was a runt or two. George would usually remove the little fellow and bottle-feed it goat milk in the house. With such personalized care, the runt will usually survive. But the Class of 1990, with more than 200 piglets, had no fewer than 18 runts-so many that George and Mary had to establish a “runt stall” in the barn.

Christopher Hogwood was a runt among runts. He was the smallest of them all-half the size of the other runts. He was a particularly endearing piglet, Mary remembers, with enormous ears and black and white spots, and a black patch over one eye like Spuds McKenzie, the bull terrier in the beer commercial. But Mary was convinced he would never survive. It would be more humane to kill him, she urged, than to let him suffer. But George said—as he often does—”Where there’s life, there’s hope.” The little piglet hung on.

But he didn’t grow.

Because intestinal worms are common in pigs, George and Mary dosed the piglets with medicine to kill the parasites-and perhaps boost the runt’s growth. “The wormer didn’t do a thing for him,” Mary told us. “He probably had a touch of every disease in the barn—he had worms, he had Erysipelas, he had Rhinoneumenitis-and yet he wouldn’t die. He just wouldn’t!”

They called him The Spotted Thing. Though he didn’t die, it was unlikely anyone would buy him. Folks usually buy a pig in April to raise for the freezer, when the piglets typically weigh 50-65 pounds. Christopher weighed about 7.

Mary kept telling George, “You’ve got to kill that piglet.” George would take him out to the manure pile, intending to dispatch him quickly with a blow to the head from his shovel. But he would watch the little piglet—his soulful eyes, his big floppy ears, his admirable will to live—and George just couldn’t do it. “I must have set him out to kill that piglet 15 times,” Mary remembered. Finally George refused to even go out there. “YOU kill the piglet!” he said to his wife. Mary took the spotted runt out to the manure pile with the shovel. She couldn’t do it either.

That’s when she called my husband, Howard.

I was in Virginia. “I can’t believe I’m going to make this offer to ruin your life,” Mary began. Would we take the sick piglet?

Howard was constantly battling my efforts to stock the house with various orphaned animals. He would not let me enter the local humane shelter. We had already adopted a neglected cockatiel and an about-to-be-homeless crimson rosella parrot. When our landlords moved to Paris, we adopted their loving gray and white cat, Mika, who followed Howard and me on walks like a dog and who came when we called her. We also had two peach-faced lovebirds once, but now we were down to one. When things went wrong with our animals, it usually happened when I was away. On a morning earlier that year, one of the times I was in Virginia caring for my dad, Howard found the male lovebird, Gladstone, on the bottom of the cage, which is a bad enough sign, but on closer inspection, Howard saw that his head was missing. The female, Peapack, sat unperturbed on her perch. We renamed the female Ton Ton Macoute.

My frequent travels-sometimes I was gone for months, disappeared into some jungle, researching stories for newspapers and magazines and books—were among the reasons Howard wanted no more animals. Once I had gone to Australia to live in a tent in the outback for half a year to study emus. When I’d left, we had five pet ferrets. When I came back, there were 18 of them-and the babies all bit viciously until I tamed them by carrying them around constantly next to my skin, under my shirt-giving new meaning to “hair shirt.” Howard did not, understandably, want to get stuck caring for an arkload of creatures who would surely choose my next absence to run amuck, overpopulate, or decapitate one another.

“Normally I wouldn’t even give her the message,” Howard told Mary. “But her father’s dying, and this might be a good idea.”

What did we want with a pig, anyway? Certainly not for the freezer; I am a vegetarian and my husband is Jewish. We had always loved pigs—but who doesn’t?

After all, what is more jolly and uplifting than a pig? Everything about a pig makes one want to laugh out loud with joy: the way their lardy bulk can mince along gracefully on tip-toe hooves, the way their tails curl, their unlikely but extremely useful flexible nose disks, their great, greedy delight in eating.

When I was 6, visiting my mother’s mother in Arkansas, I had spent a blissful afternoon with a little boy hanging around his father’s pig sty. The pigs were huge and pink and made fabulous, expressive noises. I was fascinated. I apparently classed them (correctly) with horses-after all, both are hoofed mammals, although from diverging lineages within the ungulate family—because I almost immediately got on the back of one of them as if she were a pony. The pig generously let me ride around on her, almost as if I wasn’t there. This was much talked about in the dusty little cotton-growing town of Lexa, where my glamorous mother had, improbably, grown up-a place where not much more exciting than this ever happens. Later, the boy named a pig after me. I relished this honor so much that even though I never saw the boy again, I recall his name to this day—as he surely recalls mine, more than four decades later, having said it daily over the life of his pig.

Since then, my experience with pigs was limited to visits to George and Mary’s, the hog pens at local agricultural fairs, and a single meeting with our neighbor’s huge brown boar, Ben. All too soon after our meeting, though, Ben disappeared into the neighbor’s freezer.

But my husband seemed ready to embrace this new member of the family. Howard had already selected a new name for The Spotted Thing. He would be named in honor of an exponent of Early Music. The original Christopher Hogwood was a conductor and musicologist, and founder of the Academy of Ancient Music. We often listened to work he conducted on National Public Radio. So Christopher Hogwood was an apt name for several reasons. Pigs’ affinity for classical music is well-known; many an old-time hog farmer piped it into the sty to keep the pigs calm. As Howard likes to say, what earlier music is there than a pig’s grunting?

But Christopher Hogwood did not grunt that first night. His breathing was wet and noisy. His eyes were runny, and so was his other end. We had no pig medicine. We didn’t even have a proper sty. We didn’t know how long he’d live. We didn’t know how big he’d get. We didn’t have a clue what we were getting into.

How long do pigs live? This was a question we would often be asked, and our answer always shocked everyone: Six months. Most pigs are raised for slaughter, and this happens quite literally at a tender age, once they reach about 250 pounds. A few lucky sows and breeder boars will be allowed to live for years, but they, too, are usually dispatched when their productivity wanes. Even breeder boars seldom live past 6 or 7, because they become so heavy they would crush the young sows who produce the biggest litters.

Relatively few people keep pigs as pets. Those who do usually keep Vietnamese potbellied pigs. Vietnam, with a porcine population of about 11.6 million (winning top honors for most pigs in South East Asia) manages to cram so many pigs into such a small area by breeding extraordinarily small pigs—but small is a relative term when it comes to swine. Vietnamese potbellied pigs, if allowed to live to maturity at about age 5, typically grow to about 150 pounds. From Vietnamese Potbellied stock, scientists have bred even smaller pigs for research purposes-“micropigs” who might weigh as little as 30 pounds and stand only 14 inches tall, and who can make fine pets. But many pigs touted as tiny turn out to be of mixed porcine parentage and, to their owners’ horror, quickly outgrow their miniature dimensions, necessitating potbelly rescue groups like Pigs without Partners (Los Angeles) or L’il Orphan Hammies (in Solvang, California). Even the ones who stay small can mean big problems. One woman we know had to give away her Vietnamese Potbelly because he would bite whenever he thought that she or her husband were taking up too much space in their communal bed.

I could barely allow myself to hope Christopher would survive the night.