The Tapir Scientist: Saving South America’s Largest Mammal

(Scientists in the Field Series)

Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, ISBN 0547815484

Chapter 1: On The Tapir Trail

RAP-RAP-RAP!

José’s knuckles bang the roof of the car. It’s the sound we’ve been waiting for.

Crammed into research biologist Pati Medici’s 1977 Toyota Bandeirante Land Cruiser, we’ve been scanning the grass, water and scrubby forest around us for a big, dark shape. We’re in the world’s largest wetland, ten times the size of the Everglades, a place shimmering with a million shades of green and pulsing with the songs and wings of birds. Standing in the open back of the vehicle, Pati’s field assistant, José Maria de Aragão, has the best view—and now he’s signaled us he’s spotted what we came from three continents to find: a tapir (“TAY-peer”). It’s surely one the weirdest-looking and most mysterious animals on Earth.

Never heard of a tapir? You’re not alone. Even here in Brazil, most citizens don’t know what it is. In the U.S., they don’t either. When videographers visited an Orlando park in Florida to ask people what a tapir was, different folks told them it was a dangerous wild cat, a sort of monkey, and a huge bird. One person insisted it was green. Another said it lived in the tundra.

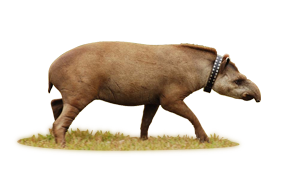

But the real tapir is more unexpected yet. A tropical animal with a long, flexible snout (which it can use a snorkel when it swims) and a stout body, four hoofed toes on front feet and three on each in back, it looks like a cross between a hippo, an elephant, and something prehistoric.

Tapirs aren’t related to elephants or hippos. Because of their flexible snouts, some people think they’re anteaters, but that’s wrong, too; tapirs’ closest relatives are rhinos and horses (they even whinny like horses do!). But the tapir is prehistoric: it has remained unchanged since the Miocene, more than twelve million years ago—a time when mastodons, sabre-toothed cats and bear-dogs roamed North America, and the first humans had not yet evolved in Africa. A lot of other things have changed since then: a land bridge now connects North and South America. Horses back then had three toes; now each leg has but one. The mastodons, sabre-tooths and bear dogs are gone. But tapirs still look much the same.

Five million years ago, tapirs lived all over Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Now they’re found only in South America, Central America and Southeast Asia. The tapir is “a survivor of a more gentle and legendary time,” as one long-ago traveler wrote, “wandering in unique isolation in a world not yet mature enough for its wisdom.”

But Pati, a petite Brazilian with a huge smile and an iron will, is eager for tapir wisdom—for soon, it might be too late. All four species of tapirs are disappearing, and that’s even more terrible since whole forests could vanish with them.

Tapirs love fruit, and because they eat in one place and poop in another, they transport the seeds in the fruits they’ve eaten far from the trees on which they grew. Pati calls the tapir “the gardener of the forest” because it “plants” (complete with fertilizer) the seeds that grow into trees upon whose fruit many other animals depend. Tapirs are too important to lose. Yet very little is known about them—including how best to best protect them.

Learning that is a job Pati takes personally. For her, conserving the forests and the animals is as important as protecting her own home.

She was born in São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil. But when she was six, her mother and stepfather, who worked for Volkswagen in Brazil, moved to a house amid a mossy, humid forest between the outermost edge of the city and Brazil’s Atlantic coast. There were few other houses, and few other kids—but loads of trees, birds, and monkeys. “I never owned a doll,” she explained. She never wanted one. “I just played in the forest,” she said. “We kids would walk the trails in the forest, build huts in the forest. I loved that.” In high school, she thought she wanted to be an architect; but then she realized she felt more at home in nature than in any building. She soon discovered that protecting the land and its animals was more important than any human-made structure she could design.

Pati started out studying monkeys. “But there were plenty of people concerned with primates,” she said. “I wanted to start something new.” In 1992, she and nine others founded Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (Portuguese for Institute for Ecological Research). They made a list of “dream animals” that needed study. “The tapir was one of these,” she said. “They’re major seed disperses, with a huge role in shaping and maintaining the forest. I wanted to know more. At that point we knew zero about tapirs in Brazil.”

Why’s that? “Because it’s so difficult to study them,” Pati explained. “They’re hard to find. They’re solitary. They are nocturnal [active mostly at night.] They’re hard to capture. It’s an animal that’s extremely difficult to work with.”

Studying them will demand everything we’ve got. We’ll follow them with the latest telemetry technology—and by looking for hoofprints in sand. We’ll search on foot, by car, and with motion-sensing camera-traps. We’ll need outdoor skills and language skills, knowledge of mechanics and medicine, and tools that range from sticks to satellites. Unraveling the secret lives of tapirs is at once like solving a detective story and a watching soap opera. As we’re about to find out, it’s a quest full of drama and challenge, mystery and danger.

For the next two weeks, we’ll be looking for the lowland tapir, the most widespread tapir of all. It’s found in most of South America’s grasslands and rainforests. (The Baird’s tapir lives in Central and Northern South America; the rare mountain tapir in South America in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru; and the Malayan tapir, dark grey except for a broad white stripe around its middle, in Southeast Asia.) Maybe even this afternoon or this evening, we’re hoping to dart one with a tranquilizer so we can photograph, examine, and outfit it with a radio collar, so Pati can track the animal’s movements—and find out, among other things, how much land each tapir needs to survive. It’s a crucial first step to protecting this fascinating, widespread but little-known species.

But first we have to find a tapir.

Just moments earlier, Pati had told us to be ready in case we do. If José knocks, “no moving, no talking until we dart the tapir,” she warned. Along with a sedative to make the animal sleep, she explained, the dart contains a radio transmitter that will allow the team to track the animal if it runs into the brush before it lies down to sleep. “We wait two to three minutes,” Pati said. “We don’t want to run after it or frighten or stress it—”

RAP RAP RAP!

At the sound of the knock, Pati raises her binoculars. Is it really a tapir? A big, dark shape might be something else. For instance, it could be a giant anteater—a toothless beast with a tube-shaped head and huge bushy tail, who can stretch seven feet long. It could be one of the four species of deer here, grazing with its head down. It could be a long, low bush.

Or it could be a cow.

A cow—wandering the wilds of Brazil?

You might not expect to find a cow in the Amazon rainforest. But you should here, in Brazil’s other great, though lesser-known, wildlife area: the Pantanal (“PAHN-tuh-NAHL”). It comes from the Portuguese word “to lick,” for here the waters are always licking the land. Stretching for 75,000 square miles during the wet season, the Pantanal is as big as the state of Florida, extending from southwestern Brazil into parts of Paraguay and Bolivia. It’s a mixture of wet, sub-tropical forests and wet grasslands nourished by more than 100 rivers. Described as “South America’s Serengeti” and “The Everglades on steroids,” it’s packed with strange and beautiful animals. From the world’s largest rodent, the capybara, to the world’s largest parrot, the blue and gold macaw, to the world’s largest gatherings of crocodiles, yacare caimans, the Pantanal swarms with superlatives.

But it’s also full of cows and horses—with some pigs, sheep and goats thrown in for good measure. Most of the Pantanal is not a national park or a nature reserve. Ninety five percent of the land here is privately owned by ranchers, whose eight million cattle share the land with the native animals. The spot we’re in now is actually a huge paddock, one of twenty, on a sixty five square mile ranch known as Baía das Pedras, whose owners welcome Pati’s study of tapirs.

Pati brings her binoculars down from her eyes. False alarm. “Um porco,” she says in Portuguese, the national language of Brazil. A feral pig.

We drive on. Each of us is eager to get a chance to do what we’ve come here for: Pati, the leader of the expedition, hopes to dart, examine and collar as many animals as possible. José has had much experience tracking tapirs with Pati through the bush for the past sixteen years. Gabriel Damasceno, with both Brazilian and American citizenship, is ready with his dart gun. Two veterinarians, Brazilian Eduardo Moreno, and Dorothée Ordonneau, a volunteer from France, are here to see if the tapirs are healthy and ensure the darting goes safely. Photographer Nic Bishop and I, Sy Montgomery, have flown in from the USA to take the pictures and write the words for this book.

Though it’s only our first day together, we’re all anxious to see a tapir—especially since it will soon be dark. The setting sun is a salmon pink ball beneath a bank of lavender clouds.

“Some of the most beautiful sunsets in the world are in the Pantanal,” says Pati, “and tonight—”

RAP- RAP-RAP!

“Tapir! Tapir! Tapir!” Pati whispers excitedly. This time, she’s sure.

We hush. The crinkling songs of frogs and insects fill the silence.

Ahead we see our quarry. The animal looks as big as a rhino—though it really isn’t. A rhino can weigh as much as a car; a lowland tapir weighs about as much as three fat passengers. Still, the tapir is South America’s largest terrestrial mammal—bigger than its biggest cats, the slinky, spotted jaguar and the stealthy, sand-colored puma. It’s an impressive, powerful beast.

The tapir stands about 300 yards ahead of us, just to the right of the sandy track. It stays perfectly still for a full minute. Then it trots across. José and Gabriel leap from the open back of the truck. Gabriel carries the dart gun; José’s job is to instruct him on how to keep track of the tapir, or herd the tapir toward him if necessary. They chase after the big animal, hunched over in a running crouch. Soon dusk swallows them from sight.

Pati folds her slender hands in her lap to wait.

We listen to the three-noted, upward-trending whistle of the grouse-like bird known here as the Jaó. Its voice sounds like a person asking a question—as we are, silently, while we wait. How many tapirs live in this area? Do any have babies? Do young tapirs grow up to live in the same area they were born, or move far away? But as the seconds tick into minutes, the insistent whistle of the Jaó seems to be voicing our most urgent question: Will we be able to catch a tapir to find out?