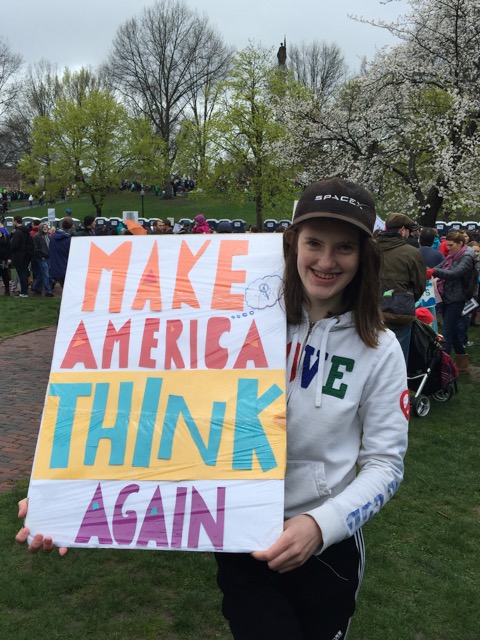

Sy spoke at the Boston March for Science. She was speaking to kids and teens, to future scientists:

Sy spoke at the Boston March for Science. She was speaking to kids and teens, to future scientists:

I want to tell you about a very special place I visited a few years ago.

It was on New Guinea—a place that has been called a Stone Age Island. Located north of Australia, it’s been known as “a lost world,” “a land that time forgot”. New Guinea was mostly unexplored by outsiders till the middle of the 20th century, for a number of excellent reasons: Tangled jungles. Steep mountains. Erupting volcanoes. Aggressive crocodiles. Poisonous snakes. Tropical diseases. Also, cannibalism and headhunting.

But because of New Guinea’s long isolation, there are animals who live here that even Dr. Suess couldn’t invent. Birds who grow tall as a grown-up, with helmets of bone capping bright blue heads. Spine-covered, worm-eating mammals who lay eggs. And kangaroos who live in trees. Real kangaroos, with pouches, who climb into towering, moss-covered trees, and then jump out of them—and bounce away!

That’s why I came—for the tree kangaroos. Working on one of my books for young readers, I joined a team of researchers trying to do what others had told them was impossible. We wanted to capture and radio collar a particular kind of tree kangaroo—the Matchie’s tree kangaroo. It’s about the size of a big cat, with orange and yellow fur and a sweet pink nose. It spends most of its time 80 feet high in the trees. It eats orchids.

Nobody had done this before.

To get to the animals we had to hike along some of the toughest trails I’ve ever done. For three days, we struggled up steep slopes slippery with sucking mud. We were up so high—10,000 feet—we were literally in the clouds. The air was thin and hard to breathe. The second day of hiking, I quietly wondered whether I was having a nine-hour heart attack.

Leading our group was my friend, Dr. Lisa Dabek. And it’s her story I want to share with you today, because this scientist is as amazing as the Matchie’s tree kangaroos she studies.Holly with carrot

Lisa always loved animals, but as a kid growing up, she couldn’t even have a dog. She had to give away her beloved cat, Twinkles, when she was 11. Why? Because she had terrible allergies, and asthma so bad she would wake in the night gasping. She couldn’t play sports. She loved nature but she lived in New York City. She wanted to be a wildlife biologist. So what could she do?

Despite her asthma, Lisa found ways to study animals as a child. She studied fish at the New York Aquarium. Fish didn’t give her asthma. Neither did the seals. At her house, on her asphalt roof of her parents’ apartment, she studied ants. Lisa let nothing get in her way.

She started traveling to New Guinea to meet them. The mountain hikes were really hard! She carried an inhaler to help her breathe. She took special pills to open her airways. But she discovered that America’s polluted air made her asthma worse. The clean air of New Guinea made it better!

Breathing, though, was only one of her problems. The second was finding the tree kangaroos. She spent weeks looking for them. The tree kangaroos were hiding because people hunted and ate them. After five weeks in the field, Lisa saw only two tree kangaroos.

And then she didn’t see another for seven years.

But Lisa kept trying. Finally she found a group who hadn’t been hunted and weren’t afraid. But up in the trees they were still hard to see. She needed to outfit them with radio collars—but everyone told her it would be impossible. People said the telemetry you need to detect the signal from the radio collars wouldn’t work in the cloud forest. There were too many trees. They’d interfere with the signal. Folks told her not to even try.

I can see how people might get discouraged trying to do something like this. At the end of every day, our little group was exhausted, bruised from falling, and wet and muddy. Once we ran out of food and had to eat ferns. Other things went wrong. Equipment didn’t work in the rain. Our satellite phone failed. We worried about the stinging nettles, and also about the leeches—they sometimes get in your eye.

But all our discomfort vanished the minute we saw our first wild Matchie’s tree kangaroo. He was even more adorable than we imagined. His colors were crazy-brilliant. His nose was the cutest, softest pink. He looked like a big stuffed animal. And his fur was as soft as a cloud.

How do I know? Because I touched it—because we captured, radio collared and tracked FOUR tree kangaroos on that trip. And today, Lisa has data on many dozens of tree kangaroos, data that is helping to save this species and the cloud forest upon which these and so many other wonderful animals—and the wise, local people—depend.

So why am I telling you about New Guinea as we march together here half a world away in Boston?

Because this story reminds us the power of what science can do. Science can change the world.

And this story also shows us what science demands of us.

Science demands we share our data. But today, much data–like on climate change–is being repressed; for political gain, many of our leaders openly deny the facts–supported by billions of data points from thousands of scientists— showing beyond a doubt that our climate is changing due to man-made pollutants. That’s bad news for tree kangaroos—and for whales and reindeer and eagles and coral reefs.

Science demands we share our data. But today, much data–like on climate change–is being repressed; for political gain, many of our leaders openly deny the facts–supported by billions of data points from thousands of scientists— showing beyond a doubt that our climate is changing due to man-made pollutants. That’s bad news for tree kangaroos—and for whales and reindeer and eagles and coral reefs.

Science can show us the solutions. But science also demands determination. And we all need to muster that determination right now—to not only gather data, but get it out there—to heal the world.

Doing science isn’t always easy. But we’re not going to quit. Like Lisa, we’re not going to back down. We’re going to keep collecting and sharing and discussing the data— we’re going to find the way to save the tree kangaroos and their forests–and our oceans, and our air, and the climate of our beautiful Earth.

Thank you.

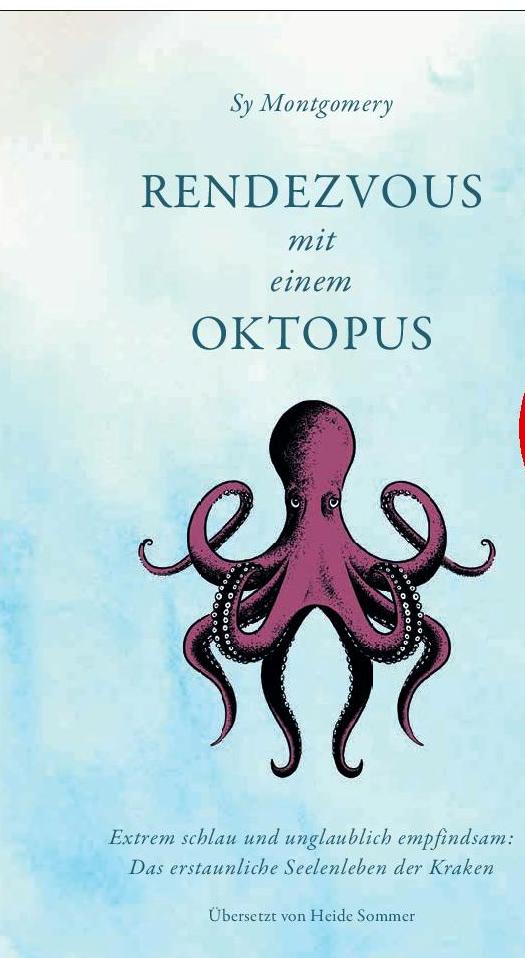

Sy is a guest blogger for the National Geographic where she asks readers to Consider the Octopus.

Octo in La La Land. The Soul of an Octopus is number 10 on the Los Angeles Times paperback nonfiction list.

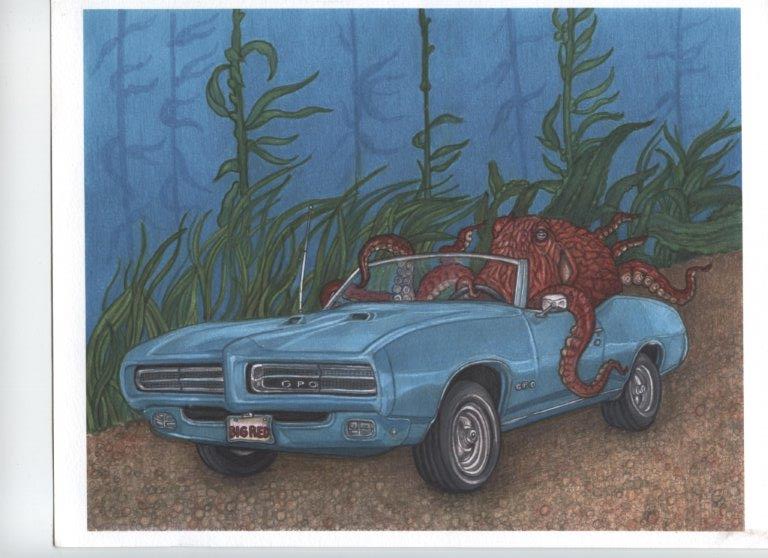

This drawing was a present from the Fishes Staff at The Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center. The Senior Aquarist, the charming Evan Culbertson, introduced Sy at the evening All Henrico Reads program. (You old Muscle Car enthusiasts will note that the Octo is at the wheel of a GPO, which is strikingly like a 1969 Pontiac GTO.)

This drawing was a present from the Fishes Staff at The Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center. The Senior Aquarist, the charming Evan Culbertson, introduced Sy at the evening All Henrico Reads program. (You old Muscle Car enthusiasts will note that the Octo is at the wheel of a GPO, which is strikingly like a 1969 Pontiac GTO.)

The Riverby Award is given to “excellent natural history books for young readers that contain perceptive and artistic accounts of direct experiences in the world of nature.” This year seven books were honored.