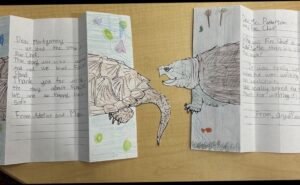

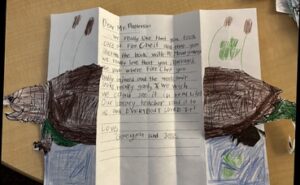

Fire Chief has mail! Children in New Castle, Washington write to him: We hope you’re doing better after your accident…. We loved the story of Fire Chief…. Do you have friends in your pond?

Fire Chief has mail! Children in New Castle, Washington write to him: We hope you’re doing better after your accident…. We loved the story of Fire Chief…. Do you have friends in your pond?

Sy enjoyed talking with Lindsey Siegele of Bioneers:

I think most of us begin life seeing animals as individuals. As children, that comes naturally. But somewhere along the way, many adults lose that way of seeing. For a long time, science itself reinforced the idea that an animal was simply a representative of its species, not a unique being. Behavioral research used to treat animals that way, and frankly, I think the researchers themselves knew it was nonsense.

That began to change in a very visible way when Jane Goodall went into the field in 1960 and refused to number the chimpanzees she studied. She named them…. Today, especially in field biology, the first thing you’re taught is to figure out who’s who. Otherwise, nothing you observe will make sense.

In that regard, I don’t think I have changed very much since I was a child. I’ve always believed animals are individuals. What can be challenging is recognizing individuality in species that are very unlike us — reptiles, or marine invertebrates, for example. But once you pay attention, it becomes undeniable. Every octopus I’ve met has had a completely distinct personality. The same is true of turtles.

Read the rest of the short interview here.

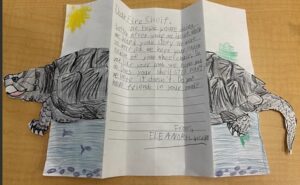

Sy talked to the Save Wildlife Organization. Here’s part of a short, insightful interview:If Sy’s philosophy has a mascot, it isn’t the octopus from her bestselling memoir or the dolphins who guided her in the Amazon. It’s a 42-pound snapping turtle named Fire Chief.

When Sy first met him, Fire Chief was recovering in a turtle hospital after being hit by a car. His shell had cracked; his tail and back legs were paralyzed. A banana dropped into his hospital tank triggered a “cruise missile” attack from the depths on the fruit.

Later, she and artist Matt Patterson were assigned to help with his physical therapy — walking him, monitoring his shell, steadying him as his nerves slowly healed.

The first time they lifted him, instinct yelled: don’t get bitten. Snapping turtles are ancient, powerful, unpredictable.

And then something happened.

“We both felt the same thing at once,” Sy says. “We could reach out and pat the head of the snapping turtle and stroke his neck.”

It wasn’t magic. It was recognition — a moment of trust exchanged across 200 million years of reptile evolution.

“You would not want to do that with a wild 42-pound snapping turtle,” she says, “but he was an individual wild 42-pound snapping turtle.”

In fifteen minutes, Fire Chief had decided they were safe.

This is Sy’s thesis in a single heartbeat: the distance between species isn’t fixed. Sometimes it collapses in the space of a gesture.

And:

Sy Montgomery has spent her life listening — to turtles, to octopuses, to dolphins, to tigers, to the childhood intuition that the world was full of minds. Her gift isn’t merely that she writes about these beings. It’s that she treats them as neighbors, not symbols; individuals, not metaphors; teachers, not props.

If her work has a mission, it is this: to remind us that we live in a world of other consciousnesses, and our lives get larger — more vivid, more connected, more whole — when we recognize them.

The rest is awe. And awe, as Sy reminds us, is everywhere.